What is Authority in Speech & Writing?

In life, authority refers to one’s power or rights. For instance, a police offer has the authority, the power, to issue speeding tickets to you if you exceed the speed limit. A judge can throw “the book” at you if you don’t pay the tickets because they are authorized to enforce the law.

In speech and writing, authority refers to the extent to which a writer or speaker’s content resonates as credible and trustworthy to its audience, be it individual readers, listeners, or a broader discourse community. In part, as welll, authority refers to

An umbrella term, authority may refer to

- the degree to which a reader, listener, or discourse community perceives a speaker or writer’s messages to be trustworthy and credible

- a writer or speaker’s persuasiveness — their ability to influence actions, opinions, and beliefs

- a measure of literacy:

- The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), a coalition of prominent U.S. college and research libraries, defines authority as a critical component of literacy. According to the ACRL, true literacy extends beyond reading and writing—it demands the adeptness to critically discern the credibility of information

- a measure of influence:

- In academic and professional writing, the authority of various sources and research methods is gauged by distinct measures of influence. These measures, from Google Scholar citations to The New York Times bestseller lists, are designed to quantify the impact and reliability of information, reflecting its significance and trustworthiness in the broader landscape. For example, Google Scholar tracks the number of times a writer is cited by other authors to determine a “Google Scholar Score”. Similarly, for web pages, Google calculates a “Page Authority Score” and offers a “Site Authority Score” for entire websites. On the literary front, The New York Times tracks bestsellers in both fiction and nonfiction categories, highlighting the most influential and popular books in the market.

Authority as a Social Construct

Authority is socially constructed: Rather than being an inherent trait, authority emerges as a product of collective agreement, influenced by cultural, historical, and social contexts. It is a byproduct of societal interactions, particularly as individuals engage in discourse and scholarly conversations.

Different academic fields, different discourse communities, have different ways of establishing authority in their speech and writing. For example, in medicine, a research article might gain authority through the meticulous execution of its study, adherence to ethical research protocols, and the thoroughness in data analysis and interpretation. It becomes particularly authoritative if the findings are published in a reputable, peer-reviewed medical journal, affirming that experts in the field have scrutinized and validated the methodology and conclusions. Additionally, if the authors have well-established reputations in their specialty and the findings are subsequently cited by other researchers, the work further solidifies its authoritative status within the medical community.

In contrast, in the legal world, lawyers often establish authority in their writing and speech through rigorous adherence to legal precedents, statutes, and specific language tailored to legal discourse. For instance, a lawyer crafting a persuasive argument might meticulously cite relevant case law, constitutional provisions, and statutory interpretations to build a compelling case. Their discourse — their writing and speech — would typically be formal, precise, and embedded with legally recognized terminologies and phrases to enhance their credibility within the legal discourse community. By aligning their argumentation stringently with established legal frameworks and using a language that resonates with legal professionals, they construct authority that is recognized and valued within judicial settings.

Authority as a Rhetorical Construct

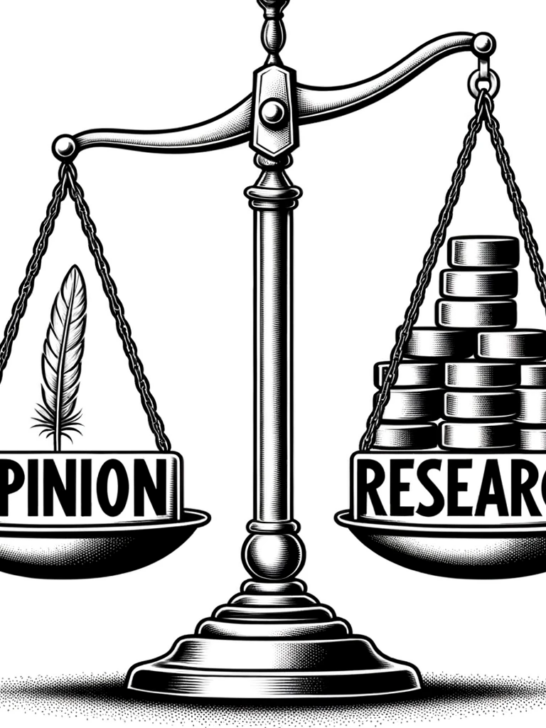

The authority a text holds is often tethered to its context. In a heated debate with a friend about which NFL team boasts the strongest defense, personal opinion and observations might carry the day. In such scenarios, the passion behind one’s beliefs and the experiences they’ve had watching games can overshadow hard statistics or expert analyses. It’s a reminder that sometimes, in the realm of personal connections and casual conversations, the heart can weigh just as heavily as the head. However, in academic and professional writing, claims grounded in research carry greater authority than claims grounded on opinion, fantasy, faith, or belief.

Authority as a Dynamic, Dialogical, Intersubjective Process

Authority in discourse, whether oral or written, emerges from the mutual interplay between the communicator (or rhetor) and the audience. It’s not just about what the rhetor believes or the audience expects; it’s a conversation where both parties continuously influence and reshape the message. Both the rhetor, with their beliefs and intentions, and the audience, with their own set of preconceptions and goals, actively shape this dialogue.

- Purposeful Calibration: Every discourse starts with an intent. The rhetor crafts a message based on their beliefs, values, expectations, and the purpose they aim to achieve. For instance, a scientist presenting a new research finding might aim to inform and persuade fellow scientists. Their message would be meticulously calibrated with data, structured arguments, and references, anticipating the rigorous scrutiny of a knowledgeable audience. This calibration ensures that the discourse aligns with both the rhetor’s objectives and the anticipated needs of the audience.

- Audience Engagement: Once the message is shared, it’s up to the audience to receive and interpret it. Their reception, influenced by their own beliefs, values, and expectations, can either validate, question, or further refine the message’s authority.

- Reciprocal Revision: Feedback from the audience can prompt the rhetor to adjust their message. Conversely, the rhetor’s refinements can lead to further reflection and engagement from the audience. This continuous dialogue ensures the message remains relevant and authoritative in the discourse.

Synonyms

Works that are acclaimed to be authoritative may be described as accurate, credible, trustworthy or powerful.

Related Concepts: Critical Literacy; Ethos; Fallacious Ethos; Interpretation, Interpretative Frameworks; Intrinsic Authority; Persona; Rhetorical Appeals; Rhetorical Moves; Substantive Prose Style; Tone; Voice.

FAQs

Why Does Authority Matter?

Because people are so busy and so overwhelmed by information, they tend to reserve their time to only read discourse that they believe is credible. Everything else is prattle — a waste of time. Meaningless chatter.

Authority is a major preoccupation of both writers and readers:

- Writers and speakers hope their audiences will find their works and their sources to be accurate, timely and trustworthy. Writers attempt to develop an authoritative prose style so their audiences will take their work seriously

- Readers, users, and other audiences question the authority of sources in order to determine if they can trust the speaker or source. Readers don’t want to waste their time filtering frivolous information. For example, Elsevier,, an academic publisher that specializes in scientific and technical fields, recently conduct a study of authority in the reading practices of professional investigators.

Elsevier randomly surveyed 3133 scientific and technical researchers from a database of 3.6 million researchers. Remarkably, they found that 37% of the respondents they surveyed distrusted half of the research outputs they’d read over the previous week. In other words, these extremely well trained researchers distrust about half of what they read–even in peer reviewed publications.

What is an Authoritative Writing Style?

The concept of authority in writing and speech is not static but evolves with societal norms, cultural shifts, and changing values. For instance, the formal, detached tone once deemed authoritative in academic and journalistic writing has given way to more personal, inclusive, and conversational styles in many modern contexts. As our understanding of inclusivity, respect, and representation grows, the language and style considered authoritative adapt, reflecting the dynamic nature of discourse and its relationship with evolving societal standards.

In contemporary discourse, an authoritative writing style tends to have 9 textual characteristics:

- Novel

- Authentic

- Nuanced and Well-Researched

- Logical and Substantive

- Well Organized

1. Novelty

Authoritative texts introduce new perspectives, research findings, theories, or methodologies. They are interesting. They provide new information. They contribute to what’s known about a topic, the scholarly conversation of humankind

- New Perspectives: Writers introduce fresh viewpoints, research methods, and research results as they engage in ongoing dialog with one another about the current status of knowledge for a particular topic

2. Authentic

- Authentic Voice: Texts may be judged to be authoritative when the writer employs a genuine, voice — and perhaps a personal voice. Readers are quick to walk away when a writer’s persona, voice, or tone feels is inauthentic.

3. Nuanced and Well-Researched

- Evidential Support: Writers furnish robust evidence for claims and ensure all assertions are substantiated.

- Source Citation: Writers provide citations for sources.They follow the citation style their readers expect them to use

4. Logical and Substantive

Authoritative works are informed by current and past scholarly conversations on a topic. They do not ignore counterarguments. They tend to investigate topics from multiple perspectives, including textual, qualitative and quantitative research methodologies.

- Detailed Insights: Writers present insights with specificity and depth, providing exact data where applicable.

- Transparent Methodologies: Writers are careful about reporting on the research methods they used to develop a knowledge claim or test Be explicit about methodologies and processes used in deriving conclusions.

5. Well Organized

Authoritative works tend to have a sense of flow.

- Writers use an organizational pattern that makes sense given their rhetorical situation

- Writers use the discourse conventions, rhetorical moves, and textual attributes their readers expect and deem appropriate for the rhetorical situation

6. Well-Written

Authoritative works follow the prose styles of academic and professional writers.

- Quality Writing: Ensure texts are not only well-written but also polished and free of errors.

- Precise Language: Writers avoid vague language and broad generalizations. Writers offer precise and detailed insights. For example, instead of saying “many people are affected,” they say, “In study X, over 50% of the population is affected . . .”

7. Ethical and Transparent

- Moral Considerations: Writers are sure to follow professional codes of conduct. They acknowledge conflicts of interest and they address ethical dilemmas or considerations as transparently as possible.

- Bias Acknowledgement: Writers are upfront about potential biases or limitations in the work.

7. Collaborative & Peer-Reviewed

Authoritative works are often the result of extended collaboration. Writers work collaboratively throughout the writing process. Co-authored texts are a norm in the sciences as opposed to the exception. Additionally, in both academic and workplace contexts, important works are peer reviewed and critiqued by experts.

8. Ethical, Inclusive and Accessible

Authoritative works not only command respect for their content but also for the manner in which they address and reference individuals and groups. Meeting professional ethical standards and codes of conduct involves using language that:

- Welcomes and Respects: Authoritative discourse ensures a tone, voice, and persona that is welcoming and conveys respect to all individuals, irrespective of their backgrounds or identities.

- Acknowledges Diversity: Such works actively acknowledge diversity, conveying respect to all people, being sensitive to differences, and promoting equal opportunities, as articulated in professional guidelines.

- Uses Inclusive Language: Ethical discourse is mindful of potentially exclusionary or derogatory terms. For example:

9. Visual and Aesthetic Appeal

Authoritative works use visual language to achieve clarity and succinctness. To advance their authority, writers use infographics, information visualizations, charts, images, and graphs. They work to make their texts visually appealing.

How Can I Assess the Authority of a Text?

Step #1: Do a Quick Assessment of the Authors & Publishers:

As a preliminary assessment of authority, take a moment to review

- the qualifications of the source’s authors.

- For example, an essay in the New England Journal of Medicine would influence most physicians’ opinions about a surgical procedure far more easily than a blog by a social influencer. Thus, it makes sense to ask

- Who wrote or published the resource?

- Is there a clear author, either a person or organization?

- What are the qualifications of the author?

- What are their academic and professional credentials?

- Do they have Master’s and Ph.D.s in the pertinent field of study?

- Do they work for a research institute, a think tank, a lobbying group, or a professional organization?

- What is their Web of Science, Scopus, or Google Scholar score?

- For example, an essay in the New England Journal of Medicine would influence most physicians’ opinions about a surgical procedure far more easily than a blog by a social influencer. Thus, it makes sense to ask

- the quality of the publisher

- What kind of publisher is it?

- A website?

- What kind of website is it? What is the URL? –.com .edu .gov .org .net

- A traditional press? a trade press? a university press? a for-profit press for people who want to pay to self publish their work? someone’s blog site?

- Is the publisher affiliated with a university? a professional organization? a national news organization? a foundation? a think tank?

- Does the publisher, whether it’s a print publication or a website, use peer review to make publishing decisions?

- Are the qualifications and professional associations of the reviewers disclosed?

- A website?

- What kind of publisher is it?

Step #2: Evaluate Authority Data

Once you’ve given a source a quick look to ascertain the credibility of the authors and publishers, you can dig in and do a deeper analysis. To jumpstart your critique, consider the following critical perspectives:

- Bias

- Can you identify any hidden agendas? Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases?

- Are there any conflicts of interest? For example, is the author funded by a business to do research on a product or service?

- What individuals or organizations support the publication? Are that organization’s purposes and goals stated clearly and openly?

- To substantiate claims, does the author rely on anecdotal information, stories, textual research?

- Peer Review

- Is the information peer reviewed? Does the publisher use peer review to make publishing decisions?

- Methodological Flaws

- Are there any problems with the research methods?

- Has the investigator used the appropriate methods?

- Has the investigator exaggerated findings?

- Communication

- Has the author employed the most appropriate writing style given the rhetorical situation?

- Citations

- Has the author cited sources?

- Do the cited sources suggest an awareness of ongoing scholarly conversations on the topic?

- Have other writers cited the resource?

- Are sources placed in conversation with one another?

- Critical & Analytical Thinking

- Given the rhetorical situation, has the author adopted an appropriate rhetorical stance? research methods? media? genre?

- Are claims supported with appropriate research?

- Are counterarguments addressed?

- Do the conclusions make sense given the research methods and research results?

- Errors

- Are there any errors?

- Citation errors?

- Standard Written English errors?

- Common Sentence errors?

- Methodological errors?

- Are there any errors?

References

Blakeslee, S. (2004). The CRAAP test. LOEX Quarterly, (31)3, Article 4.

Whitmore, M. P. (1996) Empowering students; Hands-on library instruction activities. Library Instruction Publications.