What is Inclusive Language?

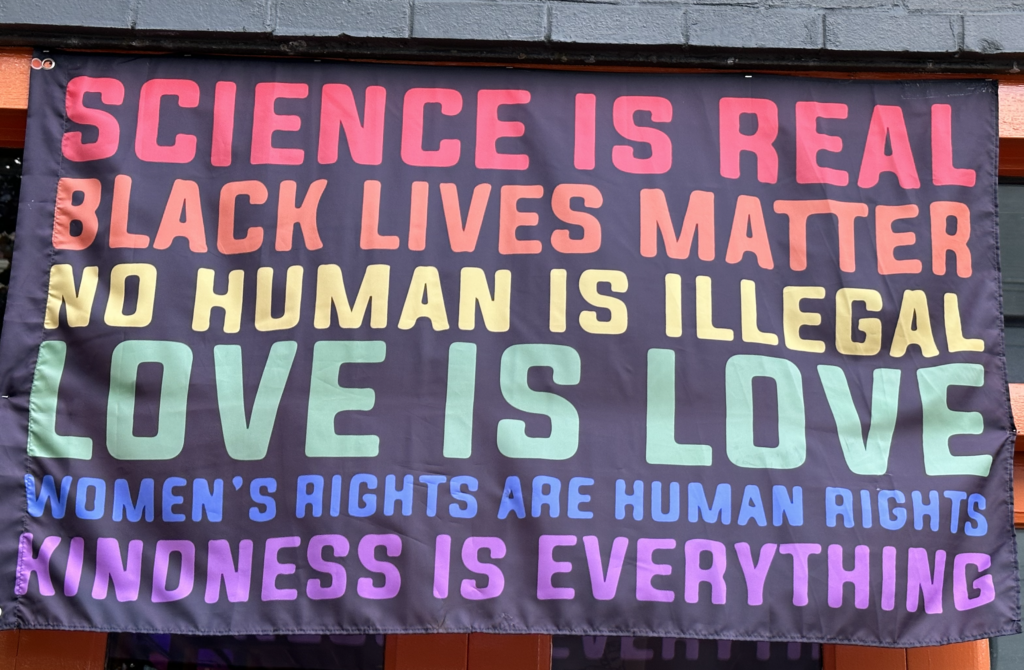

Inclusive language

- refers to language that is welcoming and respectful of others.

- is sensitive to ageism, gender, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and the values, beliefs, symbolic practices of others.

- “acknowledges diversity, conveys respect to all people, is sensitive to differences, and promotes equal opportunities” (Guidelines 2022).

- provides a welcoming tone, voice, and persona.

Antonyms: Ableist Language

Ableist language refers to language that marginalize people with disabilities as somehow deficient, other than normal.

Related Concepts: Ableist Language – Disability Metaphors – Disability Studies; Audience; Critical Disability Studies; Diction; Empathetic Information Literacy; Rhetorical Analysis; Rhetorical Reasoning; Universal Design; Usability

What Does Inclusive Language Matter?

Audiences will not read your work or will dismiss your ideas if your language is unfair and biased.

Inclusive Language meets legal, ethical, and professional standards of conduct.

Inclusive language contributes to the credibility, the ethos, of the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . .

Inclusive Language Examples

Note: Blind, Deaf, and Deafblind are capitalized

- Age, Ageism

- older adults instead of the elderly

- people over 65 instead of seniors

- Disability

- persons with disabilities or disabled individuals instead of handicapped, challenged, disabled

- persons with hearing loss instead of Deaf individuals

- those with arthritis instead of arthritis sufferers

- people with diabetes or people with depression or people with with arthritis instead of diabetes patients, arthritis patients, or diabetes patients

- wheelchair user instead of wheelchair-bound or confined to a wheelchair

- Gender

- he or she or they instead of he

- men and women instead of males and females

- humankind instead of mankind

- garbage collector instead of garbage man

- server instead of waitress

- Racial & Ethnic Identity

- African American instead of colored or Negro

- Asian instead of Oriental

- American Indian or Native American instead of Indian

- Native Alaskan or Inuit instead of Eskimo

- Hispanic instead of Spanish

- Latino instead of Mexican

- Sexual Orientation

- Partner instead of husband or wife or girlfriend or boyfriend

- Partner instead of husband or wife or girlfriend or boyfriend

- Socioeconomic Status

- people on low income or below the poverty line instead of the poor or poor people.

Gender Inclusive Language

The way we use pronouns—in particular the use of the traditionally plural pronouns they/them in reference to both males and females—has recently been a subject of intense debate. This furor over pronoun use feels very current, yet linguistic scholars trace this disagreement back at least 700 years.

The initial emergence of controversy was purely grammatical: English is lacking an important part of speech. You see, pronouns are paired with antecedents, the more specific nouns that precede them. But a problem arises when a sentence uses a singular gender-neutral common noun (like student, official, or customer) because English does not have a singular gender-neutral pronoun to pair with these words.

Example:

- If a student wishes to be excused from physical education, ________ must submit an appeal to the school board.

The available pronouns that agree in number with “student” in this example ask you to assume that students are all either male or female (“he” or “she”).

The pronoun debate that we are seeing litigated in the court of public opinion, however, isn’t really a grammatical debate so much as a social one. This is also not new. Pronouns have found themselves at the center of a values debate since the suffragist movement almost 200 years ago.

The Generic “He,” the Singular “They,” and the History of Gender Exclusive Language

In the absence of a singular gender-neutral pronoun, grammarians decreed that masculine pronouns—he, him, and his—could also be used generically to refer to both males and females. But this choice amounted to more than a fussy rule for grammar sticklers.

The generic “he” was written into law in 1871 as part of The Dictionary Act: “[W]ords importing the masculine gender may be applied to females [Statutes at Large, 41st Congress, session III, ch. 71, p. 431].”[1]The dual use of a pronoun was not unheard of (“you”, for instance, can be both singular and plural), but this dual use did create ambiguity, especially with regard to the interpretation of the law. Of particular importance is the word “may,” which signified that the courts had discretion in determining when the use of “he” applied also to women, and when it did not. Perhaps not coincidentally, prior to the passage of the Dictionary Act, in 1869 suffragists argued that if the use of the generic “he” in criminal law applied to women, then the generic “he” in voting law should apply to women as well.[2] Given that 19th amendment would not be ratified for another 60 years, this argument was clearly unsuccessful at the time. Because “he” could be either masculine or generic, it was up to our courts to interpret its use. Surprising no one, the courts determined that “he” in laws regarding punitive measures like jailable offenses and paying taxes applied generically, while “he” in laws related to the right to vote, the right to practice law, and the right to run for congress (among many others) applied only to men.

The rules regarding pronouns are inextricably tied to issues of gender and power, rights and equality.

This uneven application of the generic “he” reveals something important about the pronoun debate: It has never been a debate about grammar. The rules regarding pronouns are inextricably tied to issues of gender and power, rights and equality.

But the grammatical inconvenience of this missing part of speech resulted in calls for a gender-neutral singular pronouns predating even the suffragist movement. According to Dr. Dennis Baron, professor Emeritus and the University of Illinois and author of What’s Your Pronoun?, the singular “they” first appeared in writing in 1370 and in 1792, a Scottish economist suggested adopting “ou” as a gender-neutral singular pronoun.[3]

Dozens of recommended options have since followed, but none have had staying power:

- She/her/hers

- He/him/his

- Ze/zim/zir

- Ey/em/eir

- Per/per/pers

- Ve/vir/vis

- Fae/faer/faers

- Sie/sier/hir

In the absence of a widely accepted alternative, students were instructed, as noted above, to default to male singular pronouns in these cases.

- Example: If a student wishes to be excused from physical education, he must submit an appeal to the school board.

The generic “he,” hilariously described by Baron as “the grammatical equivalent of manspreading,” dates back centuries, and the reason for its adoption had little to do with clarity. Baron quotes John Lyly on this subject in 1567: “The Masculine Gender is more worthy than the Feminine, and Feminine more worthy than the Neuter.”[4]

More appalling than this reasoning is the fact that this solution remained the standard until the late 20th century, when the rule evolved into the more inclusive but much clunkier “he or she.”

- Example: If a student wishes to be excused from physical education, he or she must submit an appeal to the school board.

Even as late as 1985, though, only about half of editors surveyed preferred “he or she” over the generic “he.”[5] Beyond syntactic awkwardness, this option is also not fully inclusive. “He or she” excludes those who fall outside the gender binary.

Another option is to change the structure of the sentence to avoid the problem.

- Example: If students wish to be excused from physical education, they must submit an appeal to the school board.

However, writing around the problem is not always possible. The fact is that the lack of an ungendered singular pronoun is a failure of the English language, and the question of how to deal with it continues to be polarizing, with no option whipping up a fury otherwise unheard of in discussion of grammar more than the option to adapt “they” to be both plural and singular.

Critics of the use of the singular “they” have existed since its inception. Baron notes that in 1794, after being criticized by writer Don Alonzo for using the singular “they,” writers of the offending passage offered this arch reply: “With regard to our using the plural pronoun “them” . . . — as we wished to conceal the gender, we would ask . . . Don [Alonzo] to coin us a substitute.”[6] Aside from a feeble call for change in The Atlantic in 1879[7], the writing community seemed to side with Mr. Alonzo. As of 1985, newspaper and magazine editors surveyed continued to be overwhelmingly against the use of the singular “they.”[8]

Pronouns and Inclusivity Today

The tide appears, at long last, to be turning. Indeed “they” was the Merriam-Webster word of the year in 2019. Dr. Baron argues that the singular “they” is ideal, as it sounds natural enough that many people accidentally use it already and the larger writing community agrees. The Washington Post, which follows its own style guide, was an early adopter, switching to the use the singular “they” in 2015. The MLA and APA eventually followed suit to fully endorsed the singular “they” as well. The Associated Press, while still recommending writing around the need for a singular gender-neutral pronoun, has also okayed its use. The Chicago Manual of Style stops short of a full endorsement, and like the AP suggests write-arounds. They are unanimous, however, in their endorsement of using the singular “they” in reference to specific people. This is important: If a person’s preferred pronouns are they/them, the style books agree that the use of the singular “they” is not just polite but correct.

There are, naturally, still detractors. For those who argue against the singular “they” on grammatical grounds, I think it’s safe to say that they have missed the point.

First, the English language is evolving and has always done so. The rate at which words disappear from our lexicon is eclipsed only by the rate at which new words are added. 800-1000 new words are added to English dictionaries every year. Some of this has to do with objects we no longer use (like floppy disks), and some words simply become unfashionable (like groovy). Old English bears only a passing resemblance to its youngest descendant, and even early modern English seems foreign enough to induce genuine anxiety in teenagers toting Shakespeare home in their backpacks each night.

And the changes are not limited to our vocabulary—our grammar changes, too (albeit more slowly). “You,” for instance, was initially plural (along with “ye”, while “thee” and “thou” were the corresponding singular pronouns). Eventually “you” became singular as well, and supplanted the other pronouns. It is hard to understand how anyone who studies language enough to harbor strong opinions about grammar could find merit in the argument that English shouldn’t change.

Second, our language is a reflection of our culture, and this is where the real debate lives. The generic “he” emerged as a way of subjugating women, deemed “less worthy” so many years ago. It was used to write women out of the law and out of participation in public life. Today’s debate is a new version of the same song. When critics of the singular “they” insist on limiting us to “he” or “she,” it is an attempt to write everyone who falls outside of the gender binary not just out of participation, but out of existence.

But take heart. In the end, our language is not swayed by calls, no matter how fervent, to freeze in time. Our language changes as we do, and we have changed. The position of the major style books is not a harbinger of what is to come. It is a record of a change that is already here.

Recommended Resources

- Bias-Free Language. American Psychological Association, https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language. 4/20/21.

- Pronoun – Guide to Writing with Pronouns

- Pronouns and Inclusivity

- Socioeconomic status. (n.d.). Https://Apastyle.Apa.Org. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/socioeconomic-status

References

Guidelines for Inclusive Language | Linguistic Society of America. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/guidelines-inclusive-language

[1]Baron, Dennis. “On the birthday of the (legal) generic masculine, let’s declare it legally dead.” The Web of Language, 24 Feb. 2016, https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/25/331699.

[2]Ibid.

[3] Baron, Dennis. “Pronoun Showdown: Gender Neutrality and Neutral Pronouns in Language.” 11 April 2016. University of Illinois/Facebook. http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/debaron/essays/Pronoun_showdown_2016.pdf

[4] Ibid.

[5] Meyers, Miriam Watkins. “Current Generic Pronoun Usage: An Empirical Study.” American Speech, vol. 65, no. 3, [Duke University Press, American Dialect Society], 1990, pp. 228–37, https://doi.org/10.2307/455911.

[6] Baron, Dennis. “Pronoun Showdown: Gender Neutrality and Neutral Pronouns in Language.” 11 April 2016. University of Illinois/Facebook. http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/debaron/essays/Pronoun_showdown_2016.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Meyers, Miriam Watkins. “Current Generic Pronoun Usage: An Empirical Study.” American Speech, vol. 65, no. 3, [Duke University Press, American Dialect Society], 1990, pp. 228–37, https://doi.org/10.2307/455911.