Summary

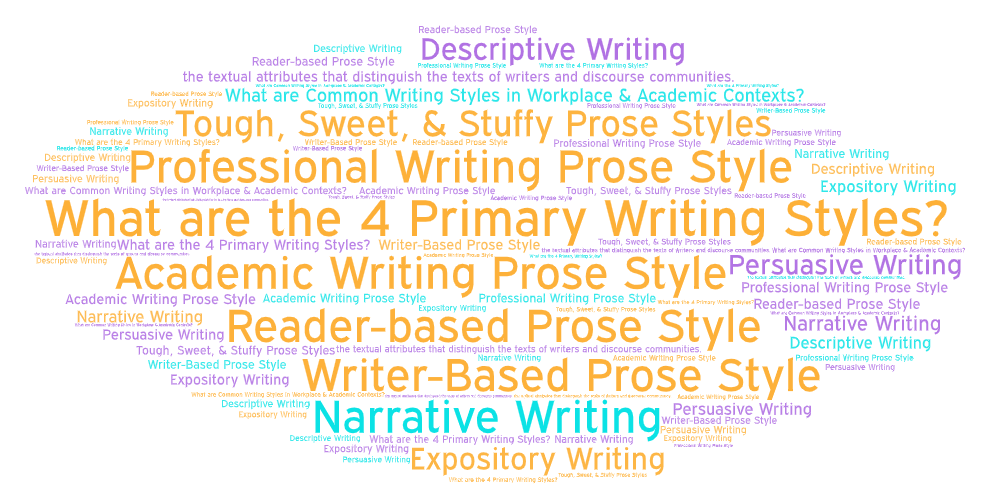

Writing Styles refers to

- different genres or modes of discourse practiced by writers and writing communities

- For example, a writer may employ a narrative style, a descriptive style, an expository style, or a persuasive style. Writing styles vary according to the rhetorical situation. identified by noting the writer’s aim of discourse and by rhetorically analyzing the textual attributes that characterize a writer’s work or the works of a community of writers–such as engineering writing or medical writing.

- a subject of study

- A corpus linguist might analyze a writer’s style by engaging in sentiment analysis: They could evaluate the writer’s s diction; use of concrete, sensory language, metaphor, similie; and figurative language.

Based on the writer’s word choice and other rhetorical devices, is the author positive, negative, neutral about the topic? Objective? Subjective? Overly emotional?

- A corpus linguist might analyze a writer’s style by engaging in sentiment analysis: They could evaluate the writer’s s diction; use of concrete, sensory language, metaphor, similie; and figurative language.

Synonymous Terms

Writing Styles may also be called

- Types of Writing, Types of Discourse

- Mode of Writing, Mode of Expression, Mode of Discourse

- Style of Expression

Related Concepts: Audience – Audience Awareness; Genre; Rhetorical Stance; Persona; Purpose; Register; The Elements of Style; Tone; Voice.

Guide to Writing Styles

In life, writers and speakers face innumerable exigencies–calls to write and speak. Each of those circumstances challenge writers (and speakers) to adopt a style of expression that the audience will deem appropriate and compelling. Thus, writers (and speakers) are likely to adopt many different writing styles during the course of their lives–and those types of writing change over time as societies and technologies evolve (more).

You can identify the style of writing of your work or the work of others by engaging in rhetorical analysis of the text. Most notably, after reading and re-reading the work, analyze the work from a rhetorical, semantic, linguistic, and visual perspective:

- Rhetorical Attributes

- What is the aim of the discourse? For instance, at the global level, is the intention of the writer to tell a story or to persuade the reader about something?

- Is the text audience sensitive?

- Semantic Attributes

- Does the writer or speaker consider the information literacy expectations of the target audience? For instance, if they are communicating in an academic context, does the author’s review of ongoing scholarly conversations about the topic demonstrate an awareness of the critical reading [practices of educated audiences? Does their text suggest they are careful to consider the accuracy, authority, context, currency, purpose, and relevance of information (e.g., textual research or empirical research)

- Linguistic Attributes

- Does the author employ Standard Written English?

- What register does the author use? Formal or informal diction?

- Visual Attributes

- What information visualizations does the writer provide? Pictures? Charts? Figures? Graphs? Tables? Data visualizations? Infographics?

Style & Aims of Discourse

Writing styles are often identified by sorting texts by the aim of discourse. For example, in A Practical System of Rhetoric, a rhetoric textbook first published in 1827 and then used religiously by American students for about 60 years, Samuel P. Newman argues that people engage in communication to achieve four primary aims:

- to tell stories

- to describe ideas, events, and people

- to educate, to inform

- to persuade.

When writers and speakers compose texts to achieve these aims, they produce four different types of writing:

- Narrative Writing – Narration

- Descriptive Writing – Description

- Expository Writing- Exposition

- Persuasive Writing – Persuasion

Following Newman, generations of teachers have taught these aims of discourse in their classrooms.

| Writing Styles | Purpose/Aim | Topoi – Textual Attributes | Genres – Examples |

| 1. Narrative Writing | share stories, experiences, reflections | setting; characters; conflicts; rising action; climax; conclusion | Autobiographies; Fiction Novels; Anecdotes; Jokes; Memoirs; Presentations; Short stories |

| 2. Descriptive Writing | help readers imagine | concrete language, sensory language; figurative language; metaphors & similes | Poetry; Problem Definitions; Sports Reporting |

| 3. Expository Writing | to inform, to explain | textual evidence; empirical evidence; citation | Academic Writing Prose Style; Professional Writing Prose Style |

| 4. Persuasive Writing | to influence, to persuade | claims; evidence; warrants; qualifiers; backing | Advertisements; Cover Letters; Editorials; Proposals; Letters of Recommendation |

Rhetorical Modes

In the rhetorical tradition, narration, description, exposition, or persuasion may be known as

Yet the terms rhetorical mode or modes of discourse are typically reserved for instances when a part of a writer’s text is discussed as opposed to the whole text. For instance, writers and speakers may use description and narration to compose some paragraphs and sentences in a text yet when that text is viewed as a whole it may be judged to be persuasive or expository.

Aims of Discourse

Building on the shoulders of Samuel P. Newman’s work, James L. Kinneavy (1971) postulated there are four primary aims, or purposes, for communication:

| Expressive Discourse | e.g, personal journals |

| Referential Discourse | e.g., scientific, informative, and exploratory discourse |

| Literary Discourse | e.g., novels, poems, short stories |

| Persuasive Discourse | e.g., proposals, advertisements, recommendation reports |

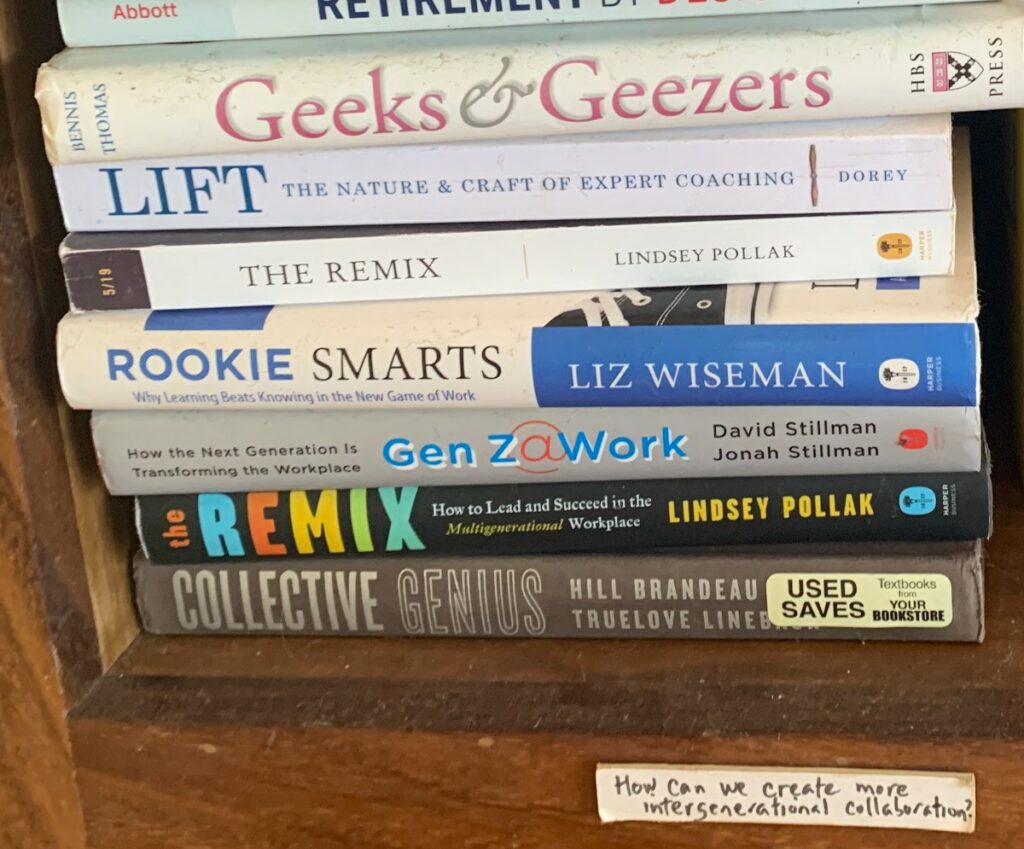

What are Common Writing Styles?

Just as the primary colors (white, black, red, yellow, and blue) may be used to create a kaleidoscope of colors, so too can the primary writing styles be blended and remixed to create new styles.

Because life is complicated, writers may have many more reasons for communicating than suggested by the four primary writing styles. For instance, writers may compose documents to

| Record | Keep a record of events or information |

| Reflect/Explore | Write in a journal, attempt to make sense of something or to shape a new idea |

| Inform: | Objectively report an event. |

| Demonstrate Knowledge | Prove, in school, that you’ve learned course content. |

| Summarize | Report someone else’s words, theories, and research in your own words |

| Explain | Help readers understand a difficult concept, theory, or event |

| Analyze | Break down a problem into parts |

| Persuade | Change minds, invoke action |

| Theorize | Speculate on possible causes and effects |

| Entertain | Bring joy, amazement, and thrills |

Academic Writing Prose Style

Academic writing is often portrayed as a monolithic form of discourse. For instance, Ronald suggests “[m]any professors believe that you should be learning to write one certain kind of style in college, one that’s objective, impersonal, formal, explicit, and organized around assertions, claims, and reasons that illustrate or defend those claims” (Ronald 1999, p. 175).

In practice, however, academic writing may be more varied, more robust, and more open to stylistic play than these portrayals suggest. Thanks to new writing spaces such as Twitter, WordPress, YouTube, and Instagram, academic writers have new opportunities to express themselves–and the affordances of those technologies tend to favor the first person and individual expression. Additionally, at least in the humanities, use of the first person is becoming more commonplace.

Textual Attributes of Academic Writing

- Research-based

- Thoughtful, well reasoned, detailed

- Reflective, self-critical

- Formal in style and tone

- Thesis-driven & deductively organized

- Respectful of copyright and intellectual property

Recommended Resources

- First-Person Point of View

- Using First Person in an Academic Essay: When is It Okay?

- A Synthesis of Professor Perspectives on Using First and Third Person in Academic Writing

Professional Writing Prose Style

The writing styles of professional writers tend to vary across communities of practice. For instance, the writing style of a lawyer is quite different from that of an accountant or a mathematician. However, across work contexts, there are a number of textual attributes and rhetorical constraints that tend to characterize the texts of professional writers.

- Rhetorically Sensitive

Professional writing is fundamentally transactional: usually if you are writing you are trying to solve some kind of a problem. Your audience — the people you are writing to — probably need to do something in response to your writing. They may not be expecting your writing. They probably don’t want to read your writing. Your writing is interrupting their day. So, if you’re gonna bother them you need to make it worth their time.

Thus, professional writers tend to focus first and foremost on what they want the reader to think, feel, and do. The audience for professional writing tends to be coworkers, clients, employers.

Typically in workplace contexts the audience is less informed about the topic than the writer. Often knowledge workers are endeavoring to simplify complex information to less informed audiences. They write from the persona of a subject matter expert, and their aim is to present information as simply as possible. - Accessible

- Professional writers’ #1 goal is to create clarity. To achieve clarity, they

- adhere to the conventions of standard written and spoken English

- organize information deductively

- adopt universal design principles

- adhere to principles of brevity, flow, inclusivity, simplicity, and unity

- use extensive elements of visual language, such as photographs, data visualizations, and infographics

- Professional writers’ #1 goal is to create clarity. To achieve clarity, they

- Concise

- To promote clarity and readability, professional writers are as concise as possible. They endeavor to strip away any unnecessary information.

- To promote clarity and readability, professional writers are as concise as possible. They endeavor to strip away any unnecessary information.

- Substantive

- Professional writing tends to be truthful and evidence based. Readers and users of professional documents need to be confident that they can rely on the information being provided.

Writer vs. Reader Based Prose Style

In Writing Studies, Linda Flower (1979) proposed a categorization schema for discussing student writing that is wildly popular in the U.S among the writing studies community:

For Fowler, a reader-based prose style “creates a shared language and shared context between writer and reader” whereas a writer-based prose style uses abbreviated, self-centered, informal, vague language—i.e., language that is personally meaningful to the writer but not the reader.

Tough, Sweet, Stuffy Prose Styles

For Walker Gibson, the universe of discourse “can be seen as an adjustment or compromise among these three styles of identifying ourselves and defining our relation with others”:

- The Tough Talker

- The Sweet Talker

- The Stuffy Talker.

How Can I Adopt an Appropriate Style?

You can determine the best writing style for a given rhetorical situation by engaging in the following composing strategies:

- Identify the register.

- Determine how formal you need to be by engaging in rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning

- Find out if you need to follow any particular style sheet, templates, or citation style.

- Companies often invest significantly in branding, and that branding includes guidelines for templates, logos, and images.

- Adopt a rhetorical stance

- Determine your perspective, point of view, persona, voice, tone

- Consider diction

- Use of figurative language

- use of Metaphor, Personification, Simile—these elements of figurative language can help your readers can better imagine and visualize your message

- Eliminate archaisms, biased language, clichés, jargon

- Be aware of the connotations of your words and idioms.

- Use of figurative language

Related Concepts

Examples of Research and Theory on Style

Ray, Brian. (2015). Style: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. Parlor Press; The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/referenceguides/style/

References

Ronald, K. (1999). Style: The hidden agenda in composition classes. In W. Bishop (Ed.), The subject is writing: Essays by teachers and students (pp. 167- 82). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.