What are Problem Solving Strategies for Writers?

As an alternative to imagining the writing process to be a series of steps or stages that writers work through in linear manner or as a largely mysterious, creative processes informed by embodied knowledge, felt sense, and inner speech, Linda Flower and John Hayes suggested in 1977 that writing should be thought of as a “thinking problem,” a “problem-solving process,” or “cognitive problem solving process”:

“We frequently talk of writing as if it were a series of independent temporally bounded actions (e.g., pre-writing, writing, rewriting). It is more accurate to see it as a hierarchical set of subproblems arranged under a goal or set of goals. The process then is an iterative one. For each subproblem along the way — whether it is making a logical connection between hazy ideas, or finding a persuasive tone — the writer may draw on a whole repertoire of procedures and heuristics” (Flower & Hayes, 1977, p. 460-461).

Examples of Problem-Solving Strategies

- Rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning

- Cognitive strategies

- Engage in logical reasoning

- Engaging in the information literacy perspectives and practices of educated, critical readers

- Interpersonal Strategies

- Collaboration

- Working with others during the writing process, such as brainstorming ideas together, collaborating on a draft, or writing as part of a team.

- Peer Review:

- Sharing drafts with peers and giving each other constructive feedback. This can help writers see their work from different perspectives and identify areas for improvement that they might have overlooked.

- Mentorship:

- Seeking guidance from more experienced writers or instructors, such as a teacher, tutor, or writing center consultant. This can involve discussing writing challenges, getting feedback on drafts, or learning new writing strategies.

- Discussion:

- Talking through ideas with others before and during the writing process. This can help writers clarify their thoughts, explore different viewpoints, and generate new ideas.

- Negotiation:

- Audience Awareness:

- Considering the needs, expectations, and perspectives of the intended readers. This can influence many aspects of the writing, from the overall structure and argument to the choice of language and examples.

- Collaboration

- Intrapersonal Strategies

- Goal-setting

- Defining what one wants to achieve with a piece of writing, be it a specific grade, clarity of argument, or a certain word count.

- Self-motivation:

- Finding ways to stay motivated during the writing process, such as breaking the task into manageable pieces, rewarding oneself after reaching certain milestones, or focusing on the value and relevance of the task.

- Self-regulation:

- Managing feelings of frustration, anxiety, or boredom that may arise during the writing process. This might involve taking breaks, practicing mindfulness, or reframing negative thoughts.

- Time management:

- Organizing one’s time effectively to meet deadlines and avoid last-minute stress. This might involve creating a writing schedule, setting aside specific times for writing, or using tools like timers or apps to stay focused.

- Self-reflection:

- Regularly reflecting on one’s writing process and progress, identifying strengths and areas for improvement, and making adjustments as necessary.

- Self-evaluation:

- Critically reviewing one’s own writing to identify potential improvements, before getting feedback from others.

- Goal-setting

- Metacognitive strategies

- Thinking about one’s own thinking or writing process involves setting goals, self-monitoring one’s progress, and adjusting tactics as needed.

Review of Research

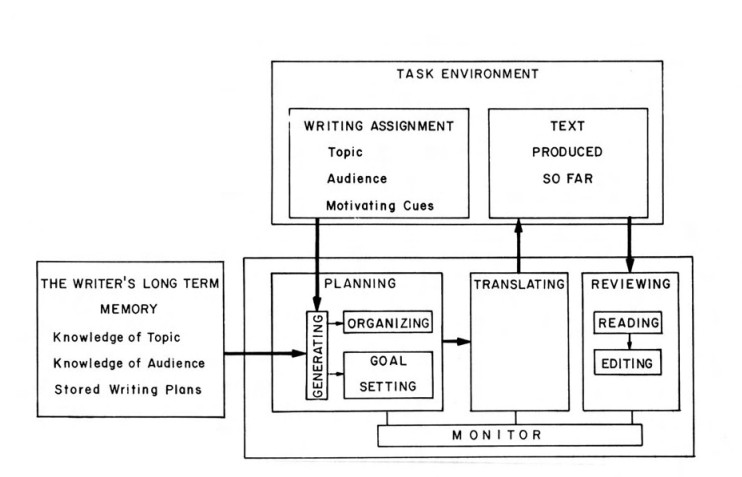

Initially, in 1977, the problem-solving model was fairly simple: it focused on the writer’s memory, the task environment (aka the rhetorical situation), prewriting, and reviewing. By 2014, following multiple iterations, the model had become more sophisticated, adding layers of complexity, such as the writer’s motivation, their knowledge of design schemas (given the visual turn in writing), their intrapersonal and intrapersonal competencies, and their access to production technologies (aka, new writing spaces).

In 1980 Hayes and Flower introduced their cognitive process model in “Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes.” Then, in 1981, they elaborated on that model in “A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing,” an article published in College Composition and Communication, a leading journal in writing studies.

As suggested by the above illustration, Flower and Hayes conceptualized the writing process to be composed of three major cognitive activities:

- planning – Writers set goals and establish a plan for writing the document.

- translating – Writers translate thought into words

- reviewing – Writers detect and correct “weaknesses in the text with respect to language conventions and accuracy of meaning” (p. 12).

They also introduced the concept of a “monitor” to account for how writers switch between planning, translating, and reviewing based on the writer’s assessment of the text.

Later, in “Modeling and Remodeling Writing” (2012), provided a more robust, complex model of the writing process. In his revision, Hayes omitted the concept of the monitor and he suggested that composing occurs on three levels:

- Control Level

This level addresses (1) the writer’s motivation; (2) their ability to set goals (plan, write, revise); (3) their familiarity with writing schemas; (4) their current plan - Process Level

This level focuses on (1) the task environment and (2) the writing process itself, detailing the interactions between the writer, the task, and the context in which writing occurs.

Writing Processes: 1. The Evaluator (e.g., a teacher, boss, or client); 2. The Proposer; 3. The Translator; 4. The Transcriber.

Task Environment: 1. Collaborators & Critics; 2. Transcribing Technology; 3. Task Materials, Written Plans; 4. Text Written So Far - Resource Level

The level concerns the resources writers need to compose: 1. Attention, 2. Working Memory, 3. Long-Term Memory, 4. Reading. T

This level includes- working memory, which is responsible for temporarily storing and manipulating information during the writing process

- long-term memory, which stores knowledge about language, genre conventions, and prior experiences with writing tasks

- attention, which allows writers to focus on specific aspects of the task while filtering out irrelevant information

- reading, which references the writer’s literary history, what they’ve read and how conversant they are with ongoing scholarly conversations about the topic.

Some key differences and improvements in the 2012 model include:

- Expanded cognitive components:

- The 2012 model introduces additional cognitive components, such as working memory and motivation, which were not explicitly addressed in the original model.

- Emphasis on social aspects:

- The 2012 model endeavors to account for the social aspects of writing, including collaboration and communication with others during the writing process.

- Recursive and iterative processes:

- The original Hayes-Flower model presented the writing subprocesses (planning, translating, and reviewing) in a linear fashion. However, the 2012 model emphasizes that these processes are recursive and iterative, meaning that writers continually move back and forth between these stages as they write, revise, and refine their work.

- Integration of technology:

- The updated model aims to addresses the impact of digital technologies on the writing process, acknowledging that the use of computers, word processing software, and online resources can significantly influence how writers plan, compose, and revise their texts.

In 2014, Hayes, in collaboration with three other colleagues (Leijten et al. 2014), once again revised his model of the composing processes. Leijten et al. argue that writing processes have changed significantly since Hayes’ 2012 revision thanks to the development and adoption of new digital technologies. They were especially interested in online collaboration tools used in the work place.

As illustrated below, in the revised model, Leijten et al. added “design schemas” (e.g., graphics, drawings, photographs, and other visuals) to the control level. At the process level, they added graphics to the text the writer had produced thus far. They also included motivation management at the resource level to address the fatigue and conflicts that can set in during long projects involving many steps and people. Perhaps most importantly, they added a searcher to the writing process to account for how open the writer is to strategic searching or how open they are to new information that contradicts previous information.

A Fun Exercise

One of the takeaways from research on writer’s composing processes is that we’re all special snowflakes: we each have our unique processes for generating, research, and writing.

To gain some insight into your own writing processes, why not draw it?

- Get your crayons out or whatever writing tools you use to draw.

- Draft your own vision of the writing process.

- Write a narrative that explains your drawing.

References

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive Processes in Writing: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369-388. https://doi: 10.1177/0741088312451260

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

Leijten, Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3