Writers must have a clear sense of to whom they are writing (the audience) and what the audience’s values and/or opinions related to the topic are.

Imagine a history professor who opens her lecture on the Victorian era by asking her undergraduate students, “Did you see the Victorian-era furniture on Antiques Roadshow last night?” Can you imagine how many in the class would raise his/her hand? Can you hear the confused silence?

To communicate effectively and persuasively

Writers must have a clear sense of to whom they are writing (the audience) and what the audience’s values and/or opinions related to the topic are. When in conversation, we often shift our tone and/or language to adapt to our audience.

Consider how you talk differently to young children than you do to your professors. When communicating with a child, you may use simple language and a playful or enthusiastic tone. With your professors, however, you may try out academic language, using bigger words and more complex sentences. Your tone may be more professional than casual and more critical than entertaining.

For example . . .

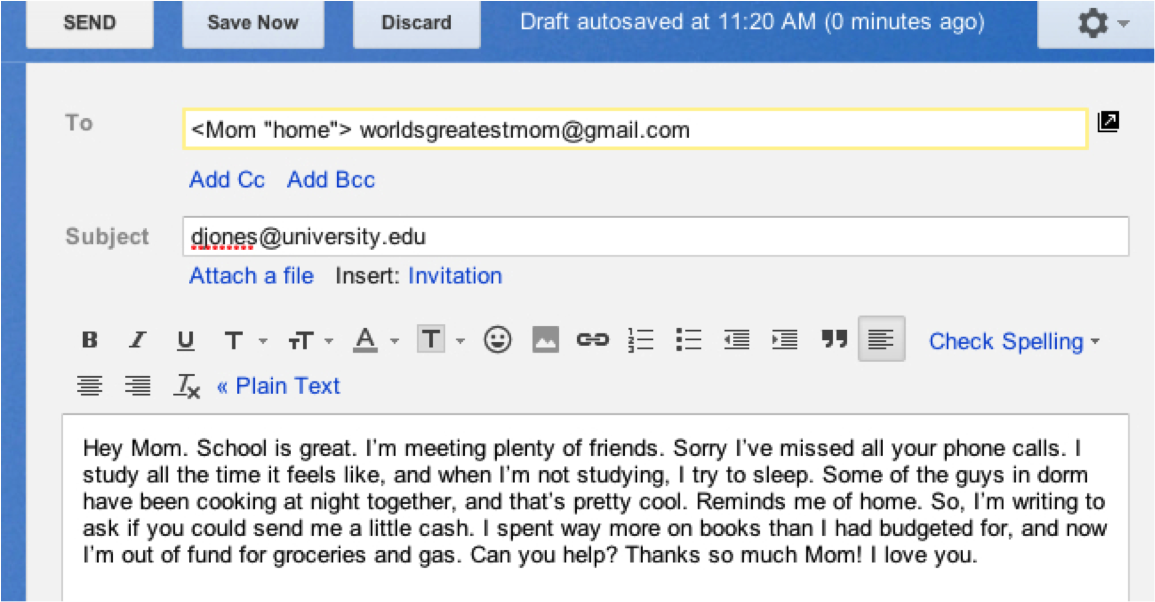

Imagine that you need money. When you craft an email to your parents asking for money, your approach might be different than if you were to ask your roommate for money. Your tone, language, and means of appeal will adapt to who your audience is.

- The tone of your email is casual, conversational, and upbeat (“School is great!”).

- The language that you use is simple, easy to read. Sentences are short and rely mostly on action verbs.

- You appeal to your parent first by recalling positive memories of home, as though you know your mom is missing you (“reminds me of home”). This is a tug at the heartstrings (or pathos appeal). By offering specific details about the cost of your chemistry textbook, you make a logos appeal (to her sense of logic). You also highlight your responsible nature, which develops an ethos appeal: “I study nearly all the time,” “I try to sleep,” and “books [more than] I budgeted.” Telling your mom that books were more expensive than you imagined links your request for additional cash to your pursuit of an education, something that makes her happy and that adds to your credibility.

For more information about ethos, pathos, and logos, see “Rhetorical Appeals.”

- When asking your roommate for cash, the tone may remain casual though it will appear less conversational. I mean, after all, you talk to this person every day. Also, noting “I’m totally okay with” buying two rounds of groceries creates a feeling of generosity rather than resentment.

- The language gets even simpler. Notice how much shorter the sentences are and how quickly the writer gets to the point; there is less need for “window dressing” your appeal. Colloquial language appears here—“could you spot me some cash”—rather than the more formal request the writer made to his mother, “I’m out of funds for groceries and gas. Can you help?”

- Reminding the roommate that you bought the last two rounds of groceries functions as an appeal in two ways: first, it establishes your credibility as a good friend; and second, it appeals to the roommate’s sense of logic (of course you need some extra money; you’ve got a free loader kind of roommate!).

A writing assignment . . .

Your professor asks you to write an academic argument paper on a topic of your choice. Academic writing is usually directed to an educated audience interested in critical, analytical thinking.

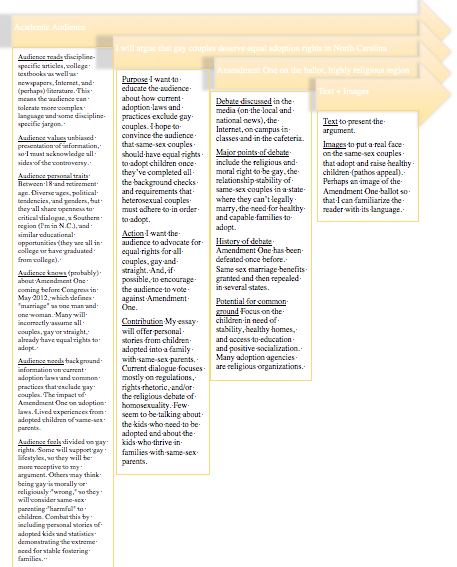

Let’s imagine you choose to write about adoption rights within the LGBT community. More specifically, you’ll argue that stable LGBT couples deserve the opportunity to adopt children just as stable heterosexual couples are allowed to do.

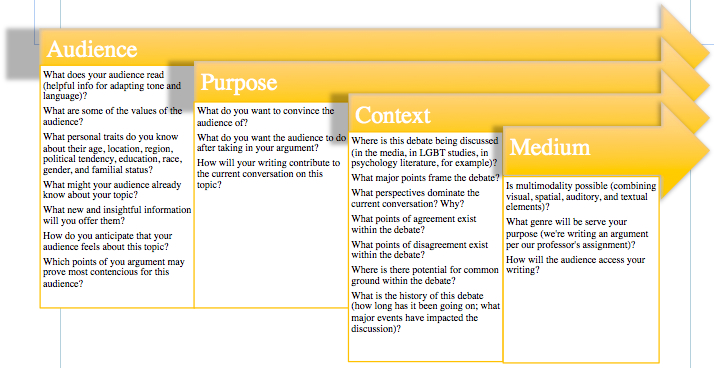

You’ll adapt tone, language, and appeals to suit the writing project’s

- Audience

- Purpose

- Context

- Medium

Brainstorming and planning

When you write to all readers, you, in fact, write to no one at all.