What is Writing Commons?

Writing Commons is an award-winning, peer-reviewed encyclopedia on writing. We publish original articles on topics of interest to students and teachers.

Writing Commons serves as an interdisciplinary reference guide and textbook for students in undergraduate writing courses, including

- business writing

- composition

- creative nonfiction

- fiction

- first-year writing

- workplace writing

- writing across the curriculum

- writing in the disciplines.

Writing Commons is an experiment on the part of the founder to investigate

- authorship, agency, and self publication (Moxley 2013, June 17; Vieregge et al. 2012)

- commons-based peer production (Benkler 2006; Vieregge et al. 2012)

- open education, copyright, and intellectual property (Moxley 2013).

- the affordances and constraints of different tools for writers.

Mission

Writing Commons aims to

- democratize access to research, theory, and scholarship in writing studies

- help writers communicate more effectively in home, school and work contexts

- help writers improve their cognitive, intrapersonal competencies, and interpersonal competencies

- help writers master 21st century literacies, including critical literacy, digital literacy, visual literacy, and information literacy

- create a forum for teachers and writers to publish peer reviewed work on pedagogical matters.

Readership

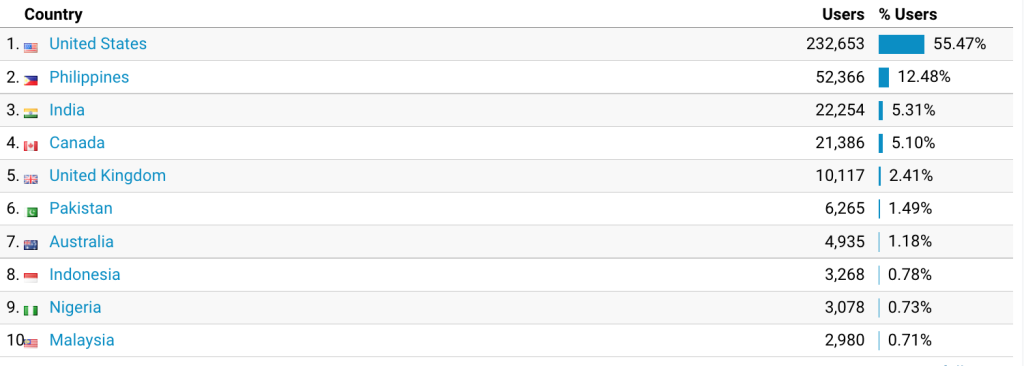

Writing Commons serves a global audience. Each year, since 2012, we have averaged over 1 million users.

Our traffic tends to be quite global, although predominantly U.S -based. According to Google Analytics, during January of 2022, readers visited primarily from the U.S., Philippines, India, Canada, and United Kingdom:

Masthead

Publisher

*Writing Commons is an independent effort from Professor Moxley’s work at the University of South Florida. Since 2008, Professor Moxley has received approval from USF to work on this project as an independent, outside activity. Writing Commons is neither affiliated with nor endorsed by USF.

4th Edition (2017 to Present)

During this iteration, we have have transformed our “free, online textbook for composition studies” into an encyclopedia for college students and professionals in the workplace. Currently, Sandy and Megan are developing Student Voices. This is a new initiative at Writing Commons that aims to provide a public form to celebrate outstanding undergraduate student writing.

Editors-in-Chief:

Cassandra Branham

Associate Professor

Director, Center for Communication and Digital Media

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

Cassandra.Branham@erau.edu

Megan McIntyre

Assistant Professor

Director, Program in Rhetoric and Composition

University of Arkansas

mm250@uark.edu

Assistant Editor

- Alexandra Watkins, Austin Community College

Assistant Editor of Social Media

- Dr. Jun Akiyoshi

Assistant Teaching Professor of English

Pennsylvania State University

Lead Copy Editors

- Jennifer Burke Reifman

Ph.D. Candidate, UC Davis - Roberto Leon

Assistant Professor, Georgia College & State University - Weijia Li

Writing & Teaching Consultant, Bucknell University

Current Reviewers and Editors

| Kelli R. Gill Graduate Student, Texas Christian University |

| Alexander Evans Ph.D. Candidate, University of Cincinnati |

| Lindsey Albracht Lecturer and Co-Director of First Year Writing, Queens College, CUNY |

| Lauren Garskie Assistant Professor and Writing Intensive Coordinator, Gannon University |

| Amber Kidd Ph.D. Candidate, Case Western Reserve University |

| Meng-Hsien (Neal) Liu Ph.D. Candidate, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign |

| Kathleen Turner Ledgerwood Assistant Professor of English, Lincoln University |

| Walter Lucken IV Ph.D. Candidate, Wayne State University |

| Flora de Tournay Doctoral Fellow and Adjunct Lecturer, The Graduate Center, CUNY, Hunter College, and Queens College |

| Walker Smith Lecturer, The University of Louisville |

| Keli Tucker Ph.D. Candidate, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Gabrielle Stecher Assistant Director of Undergraduate Teaching, Indiana University Bloomington |

| Joy Santee Assistant Professor, University of Southern Indiana |

| Anthony DeGenaro Assistant Professor of English, Ohio Dominican University |

| Kate Schnur Adjunct Assistant Professor in English, CUNY Queens College |

| Katie Baker Associate Professor of Writing, Rosemont College |

| Taylor Dickson Ph.D. Candidate, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Vanessa Cozza Faculty, Washington State University, Tri-Cities |

| Farrah Goff Adjunct Professor on English, CUNY Queens College |

| Callie Kostelich Assistant Professor, Texas Tech University |

| Jun Akiyoshi Assistant Teaching Professor, The Pennsylvania State University |

| Garrett J. Cummins Senior Lecturer, Ohio State University |

| Michelle McMullin Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University |

| Aleksandra Swatek Research Assistant Professor (NTT), Adam Mickiewicz University (Poznań, Poland) |

| Heather Shearer Teaching Professor (Writing), University of California, Santa Cruz |

3rd Edition (2012 to 2017)

For the 3rd edition, we transitioned Writing Commons from a composition textbook to an open education project for the writing studies community. We moved urls (from collegewriting.org to writingcommons.org) and set up peer-review policies and processes.

Editor in Chief:

Quentin Vieregge, Editor-in-Chief

Professor of English

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire–Barron County

As Editor-in-Chief, Quentin Vieregge developed and developed and worked with the editorial board to review submissions. During his tenure, Vieregge shepherded over a hundred articles from proposal through peer review to publication.

Advisory Board, 3rd Edition

James P. Gee

Fulton Presidential Professor of Literacy Studies

Arizona State University

James Paul Gee is a member of the National Academy of Education. His book Sociolinguistics and Literacies (1990, Third Edition 2007) was one of the founding documents in the formation of the “New Literacy Studies”, an interdisciplinary field devoted to studying language, learning, and literacy in an integrated way in the full range of their cognitive, social, and cultural contexts. His book An Introduction to Discourse Analysis (1999, Second Edition 2005) brings together his work on a methodology for studying communication in its cultural settings, an approach that has been widely influential over the last two decades.

http://www.jamespaulgee.com/

Graeme Harper

Director of the University Honors College

Oakland University

Honorary Research Professor

University of Bedfordshire (UK)

Director of the National Institute for Excellence in the Creative Industries

Bangor University/University of Wales

Graeme Harper is Director of the National Institute for Excellence in the Creative Industries and Professor of Creative Writing at Bangor. As creative writer and as cultural critic (with specific interests in film/media and the creative industries), he is a regular international speaker. He is a member of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) National Steering Committee on Practice-led Research, an honorary visiting professor (Professor of Creative Writing) in the School of Media, Art and Design at the University of Bedfordshire, Chair of the HE Group of the National Association of Writers in Education and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.

Charlie Lowe

Assistant Professor of Writing

Grand Valley State University

Charlie Lowe began began Kairosnews in order to provide a dynamic online forum for ongoing discussions about rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. It is the first community weblog in the field of rhetoric and composition, and members of the Kairosnews community produce some of the most innovative work in the fields of computers and composition and technical communication.

Mike Palmquist

Associate Vice Provost for Learning and Teaching

Professor of English

Colorado State University

Mike Palmquist is a specialist in rhetoric and composition, has taught undergraduate writing courses and graduate seminars in rhetorical theory, computers and writing, research methodology, and nonfiction writing. His research interests include writing across the curriculum, the effects of computer and network technologies on writing instruction, and the use of hypertext/hypermedia in instructional settings. His work has appeared in journals including Computers and Compositions, Written Communication, IEEE Transaction on Professional Communication, Engineering Education, Kairos, and Social Forces, as well as in edited collections.

Howard Rheingold

Visiting Lecturer

Stanford University

Howard Rheingold is an artist, designer, theorist, community builder, critic, writer, and teacher; and one of the “driving minds behind our net-enabled, open, collaborative life” https://www.ted.com/talks/howard_rheingold_the_new_power_of_collaboration. His specialties pertain to the cultural, social and political implications of modern communication media such as the Internet, mobile telephony and virtual communities (a term he is credited with inventing). He was an early and active member of the Well, as well as the cofounder of HotWired and Electric Minds, two groundbreaking web communities. More recently, he’s concerned with how collaboration is accomplished, and in particular, how media – in particular, sites like Wikipedia – are an outgrowth of our natural human instinct to work together as a group.

Shirley Rose

Professor of English

Arizona State University

Shirley K Rose is Professor of English and Director of ASU Writing Programs in the English Department on the Tempe campus, where she also teaches graduate courses in writing program administration. She directed the award-winning program in Introductory Composition at Purdue (ICaP). She also served as Assistant Head of the Purdue University Department of English. She is currently working on an analysis of results from a national survey of writing program administrators’ preparation and expectations for pursuing the scholarship of administration with her co-investigator Jonikka Charlton of the University of Texas Pan American.

George Siemens

Professor

Athabasca University

George Siemens is a strategist and researcher at the Technology Enhanced Knowledge Research Institute at Athabasca University. Formerly, he was the Associate Director, R & D, Learning Technologies Centre at University of Manitoba. He is the founder Complexive Systems Inc., an research and learning lab focused on assisting organizations develop approaches to meet the needs of changing learners, employees, and global education and business environments. Siemens has keynoted and presented at national and international conferences.

Gregory L. Ulmer

Professor

University of Florida

Gregory L. Ulmer is the author of Internet Invention: From Literacy to Electracy (Longman, 2003), Heuretics: The Logic of Invention (Johns Hopkins, 1994), Teletheory: Grammatology in the Age of Video (Routledge, 1989), and Applied Grammatology: Post(e)-Pedagogy from Jacques Derrida to Joseph Beuys (Johns Hopkins, 1985). Ulmer has authored numerous articles and chapters exploring the shift in the apparatus of language from literacy to electracy. He has given invited addresses at international media arts conferences in Helsinki, Sydney, and Hamburg, as well as at many sites in the United States.

Editors, 3rd Edition

E. Jonathan Arnett

Assistant Professor of English

Kennesaw State University

E. Jonathan Arnett is an Assistant Professor in the Professional Writing Program at Kennesaw State University, where he teaches Technical Writing, Professional Editing, and First Year Composition. His research interests include Rhetoric of Science and Professional Editing Course Pedagogy.

Matt Barton

Associate Professor of English

St. Cloud State University

Matt Barton teaches Composition and Digital Media courses at the undergraduate and graduate level. His research focuses on Digital Media, Wikis, and Video Games. He is the co-editor of Wiki Writing: Collaborative Learning in the Classroom; co-author of Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time; and author of Dungeons & Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games (A K Peters/CRC Press, 2008). He has published articles in the journals Computers and Composition, Technical Communications Quarterly, Game Studies, and several edited collections. He is also the producer of Matt Chat, a weekly YouTube program featuring interviews with game developers and historical retrospectives of classic games. Matt has an academic website, a blog, and a YouTube Channel.

Matt Balk

Instructor and PhD Student

Ball State University

Matt Balk is a PhD student at Ball State University, where he teaches First Year Composition. He is currently the Assistant Director of the Writing Center. His research interests include Social Media Usage in the Composition Classroom, as well as Synchronous Online Communication Methods.

William Carney

Assistant Professor of English

Cameron University

William Carney is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Composition Program at Cameron University in Oklahoma. In addition to Rhetoric and Composition, he has published on teaching English as a Foreign Language, varieties of English, and collaborative writing in venues such as Intercultural Communication Studies and the Journal of Language Teaching and Research. His current research interests all involve English as a Second Language and English as a Foreign Language, and he teaches classes in Technical Writing and Composition Pedagogy for English Education majors. He holds a doctorate from Texas Tech University and has earned Master’s Degrees in English and Organizational Behavior.

Joel Friederich

Associate Professor

University of Wisconsin

Joel Friederich is a poet and Associate Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Barron County in Northwestern Wisconsin. Blue to Fill the Empty Heaven, his full-length collection of his poetry, was published in 2009 by Silverfish Review Press after winning the Gerald Cable Award. He has also published two chapbooks, Without Us from Finishing Line Press and The Body We Gather from Kulupi Press. His poetry has won a Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters prize, and individual poems have appeared in journals such as Witness, Prairie Schooner, Sou’wester, The Paris Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, River Styx, and others.

Tamara Girardi

PhD Candidate

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

A PhD candidate at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Tamara Girardi teaches online and face-to-face for two community colleges in Pennsylvania. She holds a BA in English and Humanities (Jacksonville University, Florida) and an MLitt in Creative Writing (University of St. Andrews, Scotland). Her doctoral dissertation, It Can Be Acquired and Learned: Building a Writer-Centered Pedagogical Approach to Creative Writing, argues for a balance of practice and theory in daily assignments and attention to student writing and reading preferences.

Tamara writes young adult fiction, and her academic research interests include creative writing studies, online learning, student engagement, and writer-centeredness. Follow her on Twitter @TamaraGirardi

Andrea Greenbaum

Professor of English/Director of Professional Writing

Barry University

Andrea Greenbaum teaches classes in professional writing, cultural studies, gender, multimedia writing, and screenwriting. She is also the Director of the Professional Writing Program and has served on the national editorial boards of College Composition and Communication and Florida English. Additionally, she has published four books: Judaic Perspectives on Rhetoric and Composition (Hampton Press, 2008), Jews of South Florida (Brandeis University Press, 2005), Emancipatory Movements: The Rhetoric of Possibility (SUNY Press, 2002), and Insurrections: Approaches to Resistance in Composition Studies (SUNY Press, 2001). Her articles and reviews have been published in numerous journals including, The Journal of Men’s Studies, Composition Forum, Writing on the Edge, American Studies, American Jewish History, Shofar, Humor: The International Journal of Humor Research, JAC, Film and History, Florida English, and the Journal of the Assembly of Expanded Perspectives on Learning.

Heidi Skurat Harris

Assistant Professor

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Heidi Skurat Harris is an Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock where she teaches technical writing, grant writing, digital rhetoric and rhetorical theory and has developed a certificate in online writing instruction. Her research interests are online and digital pedagogy and online professional development. She also sits on the Conference on Composition and Communication’s Committee for Effective Practices in Online Instruction where she serves on the editorial board of the Online Writing Instruction Open Resource.

Stephanie Hedge

Assistant Professor of English

Stephanie Hedge is an Assistant Professor of English at SUNY Potsdam. She teaches writing courses to both undergraduates and graduate students, including digital writing, and courses on rhetoric and composition theory. Her research focuses on new media writing and digital literacies.

Mitchell Ray James

Assistant Creative Writing Editor of Writing Commons

Doctoral candidate (ABD) in the Composition and TESOL program

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Mitch James was born and raised in Central Illinois, where he received a BA in English with a minor in Creative Writing from Eastern Illinois University. He received a Masters in Literature from Indiana University of Pennsylvania and has had fiction and poetry published in Decomp, Underground Voices, Kill Author Digital Americana and Blue Earth Review among others. Mitch is a doctoral candidate (ABD) in the Composition and TESOL program at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, where he’s both an instructor in the English Department and Assistant Coordinator of the English Writing Portfolio Placement Program.

Mitch’s latest scholarly article, “Tragedy, Plot, Fiction: A Study of Sameness and How You May Have Been Duped,” was recently published in New Writing: The International Journal for the Practice and Theory of Creative Writing.

Christopher Justice

Lecturer

The University of Baltimore

Christopher Justice is a lecturer and teaches courses in Composition, Linguistics, and Literature. As a doctoral student in the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Language, Literacy, and Culture program, his interdisciplinary research focuses on Environmental Discourse, Ecocomposition and Ecoliteracy. He examines how people compose and write about the ecological “place” known as a fishery and how diverse, multimodal discourses—including literary, journalistic, cinematic, and scientific texts—influence how we conceptualize, regulate, and interact with fisheries, particularly those in the Chesapeake Bay. Other scholarly interests include Visual Rhetoric, Writing in the Disciplines, Writing Program Administration, Journalism, and Environmental Humanities. Additionally, he is a film scholar and has recently published chapters in Edgar G. Ulmer: Detour on Poverty Row, The Worlds of Back to the Future, The Films of Joseph H. Lewis, and The Cinema of Michael Haneke: Europe Utopia.

Amy C. Kimme Hea

Director of the Writing Program & Associate Professor

University of Arizona

Dr. Amy C. Kimme Hea is Director of the Writing Program and an Associate Professor in the Rhetoric, Composition, and Teaching of English Program at the University of Arizona. Her research interests include Spatial Rhetoric, Hypertext Theory, Computers and Composition, Writing Program Administration and Assessment, and Professional and Technical Writing Theory and Practice. She is on the Executive Committee of the Consortium of Doctoral Programs in Rhetoric and Composition, and at the University of Arizona, she facilitates a Faculty Learning Community on Program Assessment. Her collection Going Wireless: A Critical Exploration of Wireless and Mobile Technologies for Composition Teachers and Researchers (Hampton Press, 2009) was nominated for the Computers and Composition Best Book Award, and she has published in a range of peer-reviewed edited collections and journals in the field.

Bonnie Lenore Kyburz

Associate Professor

Lewis University

Bonnie Lenore Kyburz teaches writing, rhetoric, and digital media studies at Lewis University. A long time Sundance volunteer, film lover, performer, and rhetorician, kyburz makes short digital films that hope to resonate as entertaining, provocative arguments, especially for an evolving linguistic academic scene. Her work also appears in Composition Studies, College English, and other NCTE publications. She is currently working toward publication of her book Screen(ing) Rhetorics: Affective Digital Mediations Toward Film-Composition with the #writing series and West Virginia University Press.

Jennifer Lee Novotney

Instructor

MMI Preparatory School

Jennifer Lee Novotney teaches English at MMI Preparatory School in Freeland, PA. She has taught writing courses at Pennsylvania State University and was Coordinator of Writing at Misericordia University in Dallas, PA, where she directed the Writing Center. She was selected as a national judge for the 2012 and 2013 National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards in Writing, and she judged the Norman Mailer College Poetry Awards in 2012 and 2013. She has been a consultant for Pearson in Composition and Literature, as well. A native of Los Angeles, CA, she earned a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism from California State University and a Master of Arts in English from Northern Arizona University. She is a published author of magazine articles, poetry, and short stories. Her novel, Winter in The Soul,was published in 2014.

Angela Eward-Mangione

Professor of Literature and Composition

Hillsborough Community College

Angela Eward-Mangione is a Full-Time Instructor in the English Department at Hillsborough Community College, where she teaches English Composition I and English Composition II. Her research interests include Adaptations, Cultural Studies, and Pedagogy for Composition and Literature Courses.

Jennifer Marlow

Assistant Professor of English

College of Saint Rose

Jennifer Marlow is Assistant Professor of English at The College of Saint Rose in Albany, NY where she teaches courses in Composition and New Media. Her work focuses on Educational Technology Software and its uses in the writing classroom. When she is not busy researching Innovative Digital Technologies that bring learning “outside the box,” she makes documentaries with colleague, Megan Fulwiler, about how the labor conditions of higher education affect everything from academic freedom to student learning to how we implement and think about technology.

Patricia Portanova

Assistant Professor of English & (S.T.E.P) faculty member

Northern Essex Community College & Bentley University

Patricia Portanova is an Assistant Professor at Northern Essex Community College and a Summer Transitional Education Program (S.T.E.P) faculty member at Bentley University where she teaches first-year writing, creative writing, technical and professional writing, and linked reading/writing learning communities. She also serves as chair of the Northeast Writing Across the Curriculum Consortium and co-chair of the CCCC Cognition and Writing Special Interest Group. She holds a doctorate in Composition Studies from the University of New Hampshire and a Master’s of Arts in English from Bridgewater State College. Her current research interests include media distractions and student writing, information design, reading development, and writing assessment theory and practice.

Daisy Pignetti

Assistant Professor of Composition and Rhetoric

University of Wisconsin-Stout

Daisy Pignetti’s passion for evaluating college-level writing blossomed as she worked as a teaching assistant during her M.A. and Ph.D. programs, and continues to grow in her current position as an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Stout. While she was hired as a Rhetoric and Composition generalist, her teaching of the upper-level course, “Advanced Rhetoric,” led to a more involved role in the Professional Communication and Emerging Media program and eventually the newly created Master of Science in Technical and Professional Communication program.

A proud New Orleans native, she has presented her research on selfless and successful social media use in the aftermath of the Hurricane Katrina disaster to the Oxford Internet Institute and Association of Internet Researchers in addition to the Computers and Writing community. She has been published in Computers and Composition Online and Reflections: A Journal of Writing, Service-Learning, and Community Literacy and her book chapter on blogs is part of Hampton Press’s New Dimensions in Computers and Composition series.

Abigail Scheg

Assistant Professor of English

Elizabeth City State University

Abigail Scheg currently teaches at Elizabeth City State University. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing (California University of Pennsylvania), Master of Arts in Literature (Slippery Rock University) and a PhD in Composition (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Her research interests include Online Teacher Training, Computers and Composition, and most recently, Online Assessment. Follow her on Twitter @Abigail_Scheg

Andrea Scott

Assistant Professor of Academic Writing

Pitzer College

Andrea Scott is Assistant Professor for Academic Writing at Pitzer College, where she also directs the Writing Center. Before joining the Claremont Colleges, she taught for five years in the Princeton Writing Program and served as the Associate Director for the Writing Seminars from 2010-2013. Her research and teaching interests include Writing Center Theory, Writing Across the Curriculum/Writing In the Discipline, and the International Turn in Writing Studies. Her most recent project focuses on the Transatlantic History of the Development of Writing Initiatives and Centers in Germany since the 1990s. By examining who is creating these programs and where they are situated within the university, her research contributes new ways of understanding how disciplinary knowledge and professional identities are constructed in writing studies outside North America. She holds an Master of Arts and PhD from the University of Chicago.

Lars Söderlund

Assistant Professor of English

Wright State University

Lars Söderlund is an Assistant Professor of English at Wright State University, where he directs their Professional and Technical Writing program. His research interests include academic publishing, rhetorical theory, and professional writing program administration.

Brogan Sullivan

Assistant Professor of English

University of South Florida

Brogan Sullivan writes fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction and teaches creative writing and composition at the undergraduate level. His work has been published in Spry Literary Journal and First Inkling. His research interests include creative writing pedagogy, narratology, ethics, gender studies, and post-apocalyptic literature. He is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of South Florida.

Todd Taylor

Professor of English

University of North Carolina- Chapel Hill

Todd Taylor is a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research focuses “on how our notions of literacy are changing in response to emerging communications technologies such as the Internet” (full bio here). Todd served as the Director of the UNC Writing Program from July 2005 to July 2009, and in July 2009, he was appointed the Norman and Dorothy Eliason Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature.

Ryan Weber

Business and Technical Writing Program Director

University of Alabama-Huntsville

Ryan Weber teaches technical writing courses at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, where he directs the Business and Technical Writing Program. His research focuses on NASA and science communication, social media, entrepreneurial rhetoric, and public rhetoric. His work appears in College Composition and Communication, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, and Journal of Advanced Composition. He also runs uahtechcomm.com, a resource for technical writing practitioners and scholars. He received his Ph.D from Purdue University in 2009.

Susan Youngblood

Assistant Professor of English

Auburn University

Susan A. Youngblood specializes in Technical and Professional Communication and is co-director of the Service Learning Opportunities in Technical Communication (SLOT-C) Database. Her current research largely examines how writing—including publicly published online writing—is crafted for individuals vulnerable to physical harm, cultural harm, and exclusion from access to information and services. She studies both the tensions and processes in that communication and how that writing could be improved.

2nd Edition (2008 to 2012)

After receiving copyright back from Pearson Education, Moxley self-published the project @ http://CollegeWriting.Org. Like the 1st Edition, the 2nd Edition was solely written by Moxley.

Author, 1st Edition (2003 to 2008)

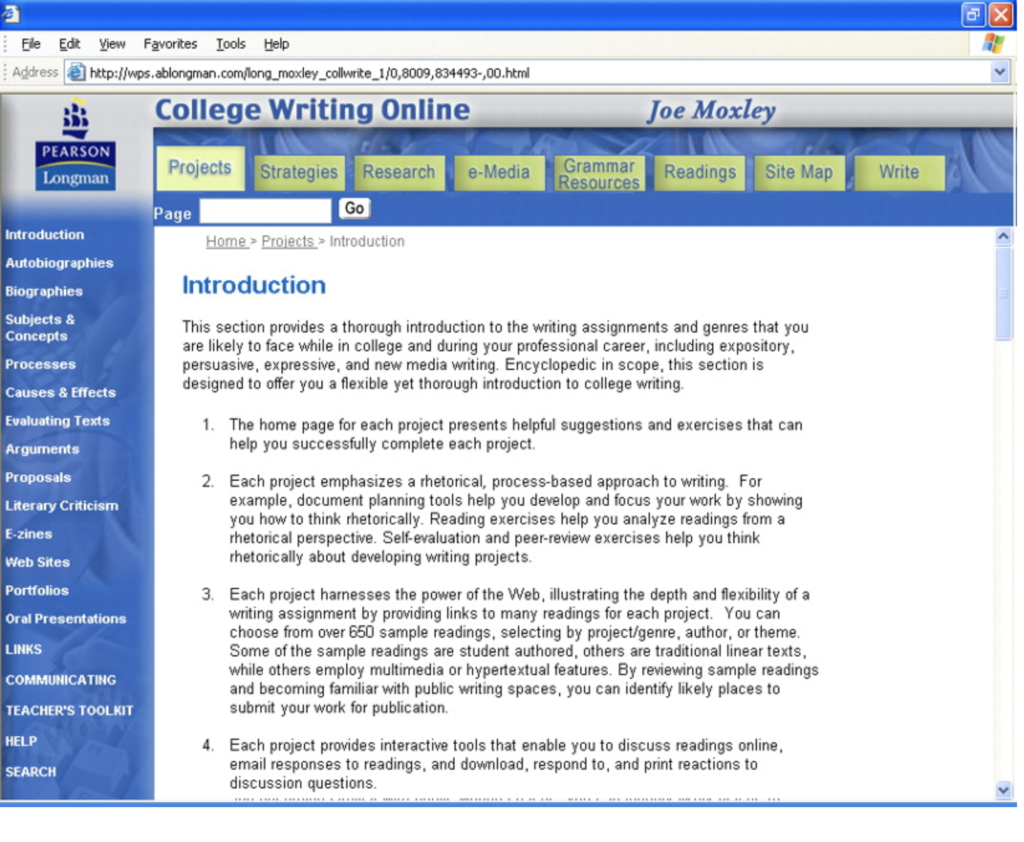

In 2003, Moxley published College Writing Online (Pearson) under a traditional copyright and commercial paywall.

Summary of Goals for Past Editions

4th Edition Goals

In 2019, we were forced to recognize that Writing Commons had evolved in ways our original menu system hadn’t originally anticipated. With the first two editions, we were a composition textbook for first-year writing. The 3rd edition branched out to fiction and professional and technical writing. This led to the fragmentation of content. For instance, we had sorted articles on audience awareness in course folders; discipline folders (e.g., technical writing, business writing, expository writing); and rhetoric folders.

On reflection, we realized the 3rd Edition was more than disorganized. We realized, in fact, that we had created the House of Lore that Stephen North satirized in The Making of Knowledge in Composition to define lore and differentiate lore from other forms of knowledge.

“The House of Lore, as it were: a rambling, to my mind delightful old manse, wing branching off from wing, addition tacked to addition, in all sorts of materials–brick, wood, canvas, sheet metal, cardboard–with turrets and gables, minarets and spires, spiral staircases, rope ladders, pitons, dungeons, secret passageways–all seemingly random, yet all connected. Each generation of Practioners inherits this pile from the one before, is ushered around some of what there is, and then, it its turn, adds its own touches. Naturally, the structure is huge, sprawling. There are, after all, no provisions for tearing any of it down. Various portions of it can and almost certainly will be forgotten and rediscovered again and again. A wing abandoned by one generation will be resettled (and may be refurbished) by another. And note, too, that there is nothing to rule out parallel discovery or re-invention, either; so the House of Lore has many rooms that look very much alike.”

(North 2006, p. 27).

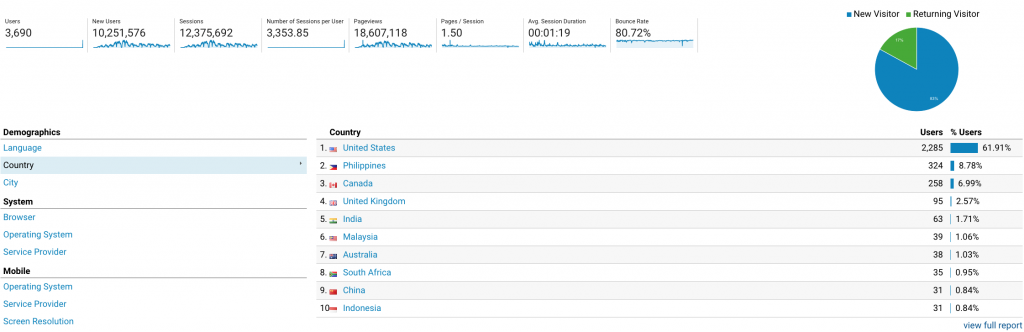

In 2019 Moxley realized we could continue as we were, adding new content and revising and editing existing content, as necessary. Or, we could detonate our house of lore—raze it to the ground and start over. Frankly, Moxley would have walked if not for Google Analytics.

On a daily basis, he was encouraged by our global traffic. As the earth spun around the sun, from our perspective in Eastern Standard Time, we could see patterns: evening readers from Asia; early morning readers from Europe. At any time of day, we could see there was always someone reading Writing Commons. On occasion, large crowds gathered.

- In 2018, we began our effort to globally revise our project by first reflecting on our rhetorical situation, particularly our audience. In other words, we engaged in rhetorical analysis of our project.

- For editions 1 & 2 we had imagined a student in undergraduate writing classes. In the 3rd edition we imagined students in academic, professional, and technical writing courses. Now we were recognizing that 50% of our traffic was a global audience. And we also noticed that most readers didn’t interact much with the text, other than the page they landed on.

- For editions 1 & 2 we had imagined a student in undergraduate writing classes. In the 3rd edition we imagined students in academic, professional, and technical writing courses. Now we were recognizing that 50% of our traffic was a global audience. And we also noticed that most readers didn’t interact much with the text, other than the page they landed on.

- Following rhetorical analysis of our Google Analytics and customer discovery, we questioned whether the textbook genre we’d employed in earlier editions constrained our organization and clarity. We hypothesized that a global audience of writers would find the convention of alphabetical order—a stable convention of the encyclopedia—to be a more intuitive organizational structure than that of a textbook, which tends to be tied to particular curriculums, historical periods, and communities of practice.

Thereafter, as we engaged in drafting and revision, we came to another hypothesis: we wondered whether the genre of the encyclopedia facilitates interdisciplinarity, a core value of the Writing Studies community. We liked how reconfiguring our project as an encyclopedia genre counterbalances the segmentation of writing studies into disparate, competing subfields.

We identified other advantages to the genre conventions of the encyclopedia: (1) the historical focus on providing all detailed information about a particular topic; (2) the scholarly tradition of paraphrasing and citing primary sources, textual research, and empirical research; (3) the tendency to historize content and show the evolution of scholarly conversations over time, - For the 4th edition, we moved from Jooma to WordPress because WordPress

- enables us to identify multiple authors for an article.

- enables us to better layer content–i.e.

- to use links and menu systems to empower the reader to go deeper, if they so wish, into research and theory

- to show associations among ideas, and

- to better understand relationships among concepts.

- To identify the thematic categories for the 4th edition, we conducted case study interviews with subject-matter experts. To explore possible organizational schemes, Cassandra Branham conducted card-sorting usability exercises with undergraduates and faculty.

- Between 2018 and 2020, Moxley wrote 376 new articles on topics of concern for writers. These articles introduce key words and concepts for writers, speakers, knowledge workers.

- We adopted a historiographical approach to many of our new articles. This involved defining the concept under discussion at the beginning of the article

- illustrating how the concept had evolved over time. (As an example of this, see Rhetorical Situation.)

- providing citations and identifying additional resources on the topic for the especially curious reader.

- From the STEM community, he foraged the concept of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cognitive competencies as a theoretical foundation for literacy.

- From Information Studies, especially ACRL (Association of College and Research Libraries), he worked with Grace Veach to update our Information Literacy resources.

- From cognitive psychology and the learning sciences, we developed new resources related to Mindset.

- For new content, Moxley decided to give authors the opportunity to choose between traditional copyright and Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. For his own contributions to the project, Moxley moved away from publishing content solely under a Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 because

- he views the encyclopedia to be a work in progress.

- By ascribing traditional copyright to his articles, he is able to avoid having old versions of his articles published.

- he was disappointed with how others were using some of his past articles. He came across instances where others did attribute him as required and yet did so in ways that he felt were a bit deceptive. Some attributions were wehidden or difficult to find. For example, some of our work had been uploaded to an e-learning platform. If you clicked through some pages you could find the attribution, but it felt a bit loosey goosey.

- he also wanted to see some rewards for his time and some ways to cover costs.

- he views the encyclopedia to be a work in progress.

- We adopted a historiographical approach to many of our new articles. This involved defining the concept under discussion at the beginning of the article

- We added Writing Studies as an entirely new section of Writing Commons.

- We wanted to give faculty who use Writing Commons examples of how the site could be used for different courses.

- Politically, we also think of our courses as a form of radical sharing—a means of pushing back against the Balkanization of teacher’s intellectual property. We invite teachers to reach a broader audience by sharing their courses and resources, which nowadays tend to be locked behind course management systems like Canvas or Blackboard.

3rd Edition Goals

The 3rd edition was published between 2012 and 2020 at https://writingcommons.org. The 3rd edition began as a modest, open-access educational resource for students and teachers of college-level writing courses, emerging from two previously published editions of College Writing Online.

At the onset, we aspired to provide the best possible composition textbook for first-year writing students — for free. Frankly, this remains a motivating factor as conventional educational resources continue to drive up costs for students, with The College Board estimating an annual cost of $1200 for textbooks and supplies in the 2019-2020 school year (College Board 2020).

Further inspired by Yochai Benkler’s (2006) work on commons-based peer production as well as the emergence of Wikipedia, we modeled the 3rd Edition after a typical academic genre: the academic journal. We created an Advisory Board and an Editorial Board and invited faculty and graduate students to submit pedagogical articles.

In 2014, after hackers attacked and took over the site in 2014 and we had to fight to reboot a new version of the site, we began incorporating ads. The ads enabled us to better fund security and server costs.

Quentin Vieregge, the Editor-in-Chief for Writing Commons between 2011 and 2017, worked with our Advisory Board and Editorial Board to

- peer review an additional 300 articles.

- encourage faculty to submit articles for creative, professional and technical writing courses

- better meet the needs of an international audience

- publish a monthly newsletter for the Writing Studies community, unCommon News

For a brief while, we piloted My Campuses. Led by Kate Pantelides, this was an effort to showcase student work. Participating schools were Malmö University, Eastern Michigan University, and the University of South Florida.

Thanks to the hard work of our review editors and advisory committee, the 3rd edition doubled the size of Writing Commons. We peer reviewed many submissions and published original works from university and college faculty and graduate students related to fiction, creative nonfiction, business writing, scientific writing, and technical writing. We were used by the first English composition MOOCs, sponsored by the Gates Foundation, Duke University, Georgia Tech, and the Ohio State University.

2nd Edition Goals

The 2nd edition was published as College Writing Online from 2008 to 2012.

Published in Joomla, a content management system, the 2nd edition was written primarily as a resource for students in college composition courses.

1st Edition Goals

The 1st edition of Writing Commons was published in 2003 by Pearson Education under the title College Writing Online. This was the first solely online composition textbook for first-year writing students. It was awarded the 2003 Distinguished Book Award from Computers and Composition.

Acknowledgements

4th Edition

We thank

- Alston Chapman for his kindness and substantive act of service in support of our mission. Throughout the 3rd edition and into the launch of the 4th edition in 2020, Alston served as our server administrator and chief tech guru. Thank you Alston for your help when we were in Joomla and for translating the site into WordPress.

- Ilene Frank, Director of Library Services UoPeople (https://uopeople.edu) for consulting with us on Information Literacy.

- Jenifer Paquette, a professor at Hillsborough Community College, for her ongoing leadership on the Style sections.

- Janice Walker, professor emeritus at Georgia Southern University, for her ongoing advice (and encouragement) regarding the organization of our encyclopedia.

3rd Edition

We thank Quentin Vieregge, UW-Eau Claire, for creating a peer-review team that offered timely and cogent feedback. Thanks to Quentin’s leadership we focused more broadly on the needs of students in professional and technical writing courses. As Editor-in-Chief, Quentin oversaw the editorial process, working with our review editors to conduct anonymous reviews of hundreds of essays.

1st Edition

Our thanks to Joe Opiela for serving as our editor for the first iteration of this text, which was published by Pearson Education.

Articles on Writing Commons

- Heron, Josh. “Writing Commons: A Model for the Creation, Usability, and Evaluation of OERs.” Composition Forum 33, Spring 2016

This is an independent review of Writing Commons. - Academe Blog

This 2014 blog, sponsored by the American Association of University Professors, addresses some of Joe Moxley’s aims for founding Writing Commons. It explores the affordances of open authorship and open education. - Moxley, J. (2013, June 17). Bending the cost curve on college textbooks. The Tampa Bay Times.

Brief editorial reports on Writing Commons as an alternative to a traditional textbook publishing. - Moxley, J. (2013). Open textbook publishing. Academe, September/October 2013. 40-43.

This article explores the genre of the textbook, the benefits of creative commons licenses, and the goals of Writing Commons. It suggests the affordances of the internet provide faculty the opportunity to self publish their own works.

References

- Benkler, Yochai (2006). The wealth of networks: how social production transforms markets and freedom (1st ed.), New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press.

- Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, N.J: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Moxley, J. (2012). An Alternative Publishing Model for Academic Textbook Authors: Open Education and Writing Commons https://writingcommons.org. Cambridge 2012: Innovation and Impact–Openly Collaborating to Enhance Education, Cambridge, UK: 16-18 April. Web.

- Moxley, J. (2013, June 17). Bending the cost curve on college textbooks. The Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved from http://www.tampabay.com/opinion/columns/column-bending-the-cost-curve-on-college-textbooks/2124156

- Vieregge, Q., Stedman, K., Mitchell, T., & Moxley, J. (2012). Agency in the Age of Peer Production. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.