Version: 4/10

Course Information1

1 Acknowledgments: I thank Heather Shearer (Teaching Professor at UC Santa Cruz) for meeting with me and sharing her expertise with labor-based grading. I also thank Asao Inoue (Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at ASU) for his research and mentorship regarding contract grading. Now that AI tools such as ChatGPT are widely available, I believe it makes more sense than every to try ungrading.

I thank Ilene Frank, Librarian extraordinaire at HCC, for her ongoing tutelage regarding all-things AI.

Spring 2024, ENC 3266, Credit Hours: 3, Department of English

Class Meeting Days: N/A. This course is delivered asynchronously.

University Course Description

Students will be introduced to the idea of research as inquiry and as a knowledge-making enterprise that is used in the workplace to solve problems or answer questions. By exploring the research methods used in the PTC fields, students will develop an awareness of how professionals in the field of professional and technical communication develop an idea, plan a research project, go about gathering data (whatever “data” may be), perform analysis, and present their work.

USF Core Syllabus Policies

USF has a set of central policies related to student recording class sessions, academic integrity and grievances, student accessibility services, academic disruption, religious observances, academic continuity, food insecurity, and sexual harassment that apply to all courses at USF. Please be sure to review these online: “>USF Core Syllabus Guidelines <usf.edu/provost/faculty-success/resources-policies-forms/core-syllabus-policy-statements.aspx>

Instructor Information

Joseph M. Moxley, Professor of English

He/Him/His

College of Arts & Sciences

Office Hours

Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2-3 p.m. and by appointment. Please email me when you have questions: mox@usf.edu. I’ll typically respond pretty quickly. If you don’t hear from me within 24 hours, pls send me a 2nd email. I’m generally available via Teams throughout the workday, especially the afternoons. Don’t hesitate to reach out. I don’t mind jumping on a call. I’d much rather have you ask sooner rather than later. We can meet online through Teams, Zoom, or Google Meet. Let me know your preference.

Welcome

Dear Students,

Welcome to ENC 3266 – Research for PTC. Below is the course requirements and schedule.

Throughout the course, at least two times each week, please check Announcements @ Canvas. I make weekly and often biweeklyAnnouncements. For instance, for the class I may clarify a student question, or I may give some group feedback on an assignment. Please email me when you have questions. I’ll typically respond back in 24 hours. If you don’t hear from me within 24 hours, pleases send me a 2nd email. If I’m online when your message comes in, I’ll jump on a quick call with you, via Zoom, Teams, or Google Meet. We can schedule longer meetings, as necessary.

My AI Policy

I am in favor your using AI tools such as Chat GPT or Midjourney. I think moving forward, like it or not, we will be working a lot with AI to accelerate communication processes. However, I strongly encourage you to develop your own unique style, voice — and thoughts.

At this point of time, it’s easy to recognize a prose style generated by AI: it tends to address content at the superficial level, it hallucinates, and it tends to follow a formulaic sentence and organizational structure. Remember, as well, that tools such as ChatGPT are founded on the greatest intellectual property theft of all time: The developers vacuumed the internet, swallowing all of that content whole. They dumped all of those words into a bucket — what corpus linguists call a corpus. Then they used statistical probability analysis to predict which letter or letters are likely to follow other letters. Then they used humans to train the dataset.

You should know that I can tell when work is based on AI and served up whole as if context doesn’t matter in clear communication. I can also determine, I believe, whether your prose has been worked though multiple iterations. Eventually, it may be impossible to discern AI prose from human prose. Presently, though, that’s not the case.

Currently, in higher education there is a great deal of conversation and debate about how professions and disciplines should respond to the usage of AI assisted writing for classroom assignments.

In my opinion, we are in a pickle: the conventions that have guided our society regarding intellectual property are shifting in response to the emergence of large language models. Professional organizations, journals, and book publishers are working on new methods for attributing sources generated from humans coauthoring with AI. Lawyers and businesses and the government are wresting with how AI can be used for the benefit of humanity. We are at a revolutionary moment when it comes to language practices. People in school and workplaces are suddenly grappling with powerful AI-informed Digital Assistants, who are capable of setting their appointments and doing routine tasks. All of this brings into question what the future is for writing and writers.

Meanwhile, though, it’s also important to note that in school settings and work settings it is a violation of academic and/or professional integrity for you to submit work that has make up sources and evidence. Thus, if you experiment with AI, you must not simply “copy and paste.” Instead, you need to check every source and quotation — really every word. So, from my perspective, it’s fine for you to work with AI but whatever you turn in needs to be yours: it needs to reflect your voice, tone, voice, persona — and thinking.

Personal Pronouns

So that I may refer to you with the appropriate pronoun in Canvas, the University’s course LMS (learning management system), please set your preferences for your personal pronoun at Canvas > Settings. If you have a first name change request for Canvas, please email IDM-Help@usf.edu from your official USF email account. You do not need to provide personal details for the request. Tell USF the first name you want to show in Canvas. This will also change your name in the directory, but it will not change your email address.

Best wishes for a productive semester.

Professor Moxley

Student Learning Outcomes

- Students will become conversant with the discourse, discourse conventions, and research methods of professional and technical communicators.

- Students will coauthor a collaborative project,

Course Delivery

This course is offered asynchronously by USF, which means it does not require real-time interactions either in person or online. Rather than convening at a specific time, this format allows you the flexibility to engage with course materials and complete assignments according to your own schedule. Below, you will find a detailed outline of the course assignments along with a schedule designed to guide you through these tasks in a timely and structured manner.

Required Course Tools – Writing Spaces

- Canvas (for grading purposes & Announcements)

- Each week, I will use Announcements @ Canvas to adjust the schedule, if necessary, clarify student questions, and give group feedback. I will ask you to upload some assignments to Canvas discussion forms and drop boxes.

- gDocs

- Zotero (for citations — unless you have another favorite app for citation management)

Required Texts

- GCF Global. Google Drive and Docs

This is a thorough, free guide to using gDocs. You’ll need this resource if you are unsure how to create and share gDocs - Web Accessibility Initiative. Images Tutorial

This is a free resource. Not sure how to caption images? Learn how to make your images more accessible. - Rewriting Work

- Syllabi Policies for AI Work

- We will study this corpus for our collaborative, class-wide project. Note this form is also available as a searchable spreadsheet

- Try This

This is the major course textbook for this course - Writing Commons

You can block the ads by adding Adblock Plus, a free Chrome extension. The ad blocker works great.

Recommended Resources

- USF Guidance for Ethical Generative AI Usage

- USF AI Resources & Tools

- Grading

Your grade will be based on your labor over the semester. This approach is called “labor-based contract grading.” Ideally, contract grading frees you up to try new things because you won’t be penalized for taking risks. In fact, I strongly (!!) encourage you to try new things and push yourself. Growth and strength result from struggle and working through confusion.

Grading Criteria

To earn an A in this course, you need to meet all of the requirements outlined above to earn a B grade AND you must work on a second project for this class that is being completed solely for this class. Choose from one of the following options. Or, if you have a better idea, tell me about it. I’d like for you to write a topic that you find interesting.

- Write in any nonfiction genre or media the equivalent of a 1000 to 1500 word article on any topic of your choice. This text should be written for a specific discourse community/magazine/journal. Even if at heart its an alphabetical text, it needs to be well designed. For instance, it should have a professional page design, be visual appealing, and include data visualizations such as infographics

- Develop a blog for a public audience. Spend the semester blogging and researching how to commercialize a blog. Research the topic you’d like to write about and the market niche. Identify leading blogs in that market. Each week write at least two 500 word posts on topics for your market/audience. Add necessary visualizations (at least one for each post).

- In the course plan below, you are scheduled to summarize and critique about five articles published in the PTC field. For this project, you would continue that work but do more of it. You’d read and summarize/critique two additional articles each week from the list of PTC articles below.

- Write a 500-word book review of a book that explores research methods in professional and technical communication. Choose from the following recently published OER books or email me if you wish to write a book review for an alternative book related to the topic of research methods in professional and technical communication:

- Engage in customer discovery research. Write a proposal for an entrepreneurial idea.

To earn a B in this course, you need to

- Turn in all but three assignments on time.

To earn a C in this course, you need to

- Complete all but five assignments on time.

To get the most from the course, I encourage you to assume an agentive mindset. Be the author. Be yourself. Find your voice. This doesn’t mean you cannot use AI, such as Chat GPT. But what it does mean is that you shouldn’t use an AI tool to do your writing for you. Remember, writing is thinking and at this point in time the AI tools aren’t capable of deep thought. Plus, you don’t want to give your agency to an AI based on information that might be suspect. If you use an AI tool, dialogue with it. Use it as a tool to help you think through the topics you’re exploring. And read its results carefully. Check sources. At this point of time, it hallucinates about 3% of the time.

Canvas Workaround

Nearly all assignments in Canvas will be marked as “Complete” or “Incomplete.” If Canvas shows you a percentage in your “Grades” view, ignore it. Any cumulative percentage that Canvas might show you is meaningless.

- You earn a score of complete on an assignment by completing it as described in the assignment description. Be sure to review the readings and other supplementary materials (e.g., rubrics, exemplars, and videos. If your submission isn’t responsive to the assignment prompt, it will not receive credit.

- You earn an incomplete by failing to submit an assignment, by submitting an assignment that does not fulfill the requirements, or by submitting an assignment that cannot be opened/read.

Late & Incomplete Assignments

Due dates. The due dates for all assignments are indicated in Canvas and in the schedule below. If you’re outside of Florida, make sure that you keep track of “Tampa Time” (EDT), as all due dates are listed according to the time zone in which the main campus is located. Most assignments are due on Monday. Take note of the following differences:

- 11:59 AM = 1 minute before noon. You probably won’t see this in our class.

- 11:59 PM or 23:59 = 1 minute before midnight. You’ll see this listed as a common assignment due-date time at Canvas.

Late assignments are those that are turned in after the due date listed in Canvas. You will not receive feedback on late work. After an assignment closes, you can no longer submit it.

Incomplete assignments are those that are not submitted, those that are submitted in an inappropriate form (for example, via email or incorrect file type) or a file that cannot be reviewed (this includes files that cannot be opened), or those that do not meet assignment guidelines or baseline criteria for passing. Incomplete assignments earn a score of “incomplete.”

No late assignments are not accepted. The only exceptions to this policy are students with USF-excused absences (medical absences require a doctor’s note; school activities such as USF teams require a note from Athletics BEFORE THE ABSENCE). You are welcome to work ahead if your schedule requires that.

Schedule

Week 1, 01/08 to 01/14 – Introduction to Professional & Technical Communication

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.” – Marcus Aurelius

The goal of this exercise is for you to visually summarize the representation of PTC competencies .

- Read

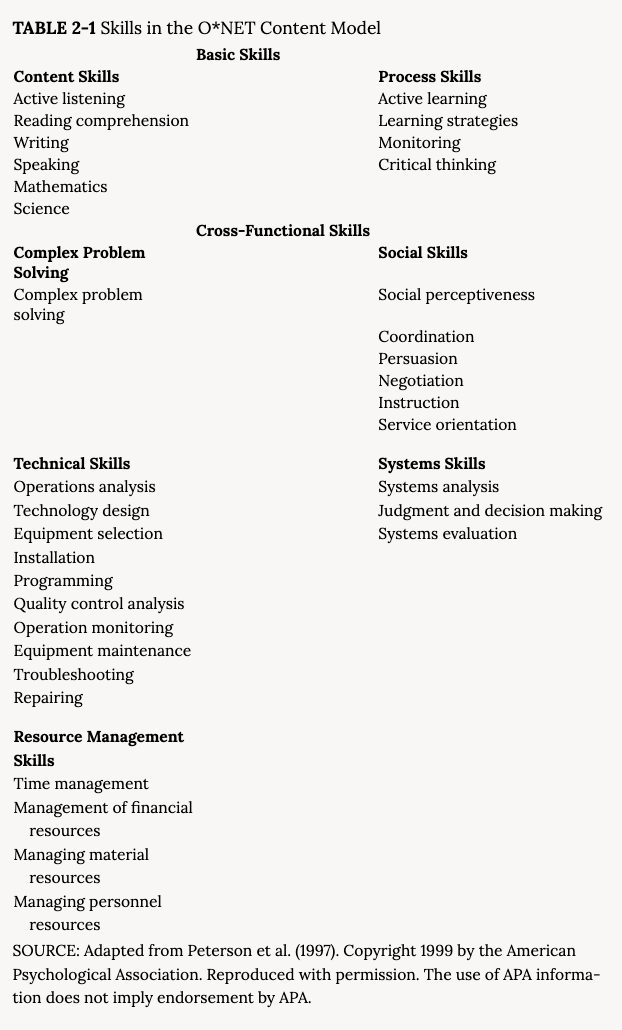

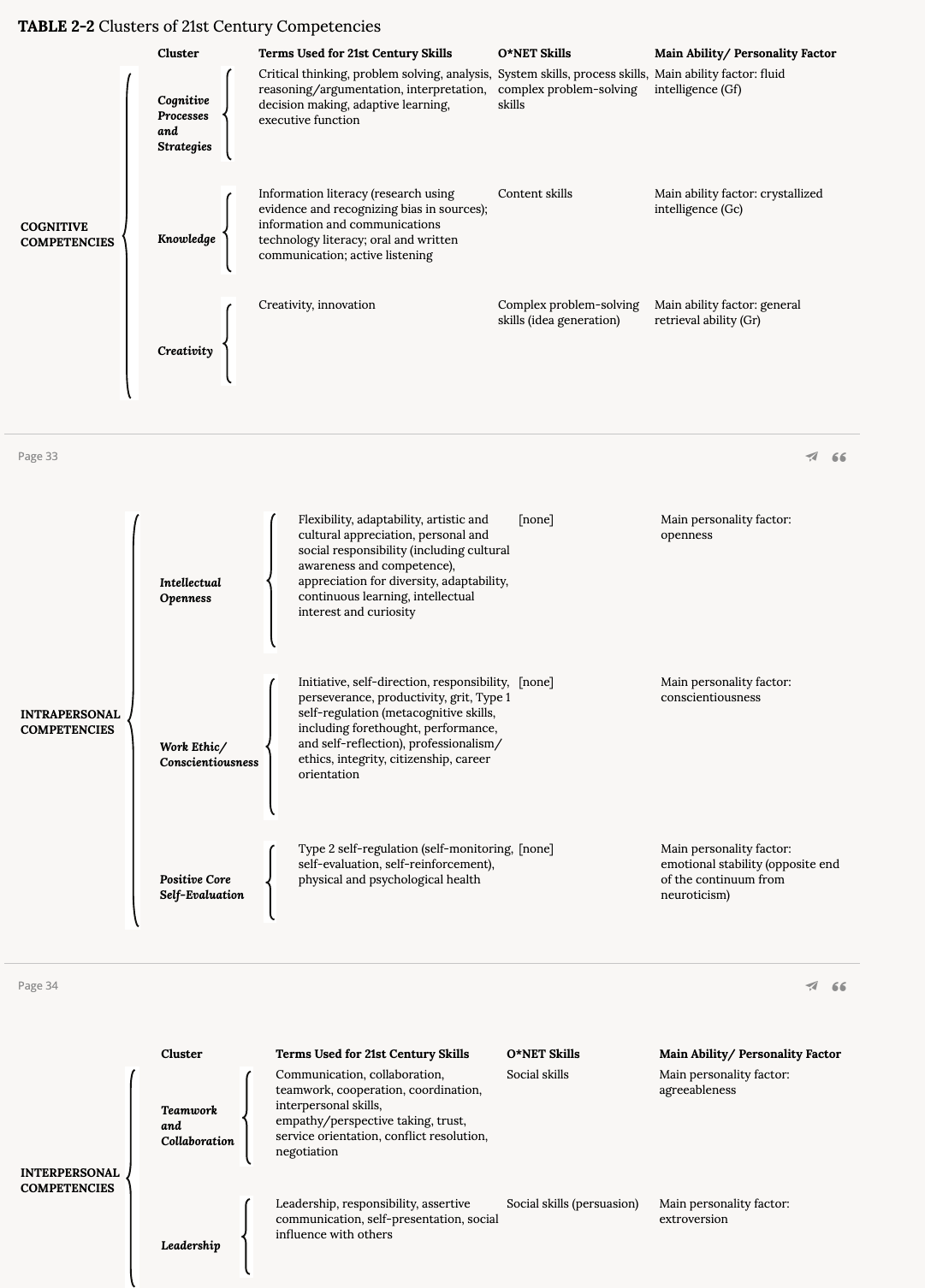

- Based on your reading of the 4 assigned readings, create an information visualization (in .pdf format) that identifies the scope of competencies a professional writer needs to do well in the PTC discipline. Your information visualization should provide the attributions for the sources you quoted, summarized, or paraphrased from. At the bottom of the visualization, you should provide the references you quoted from, summarized, or paraphrased. Use APA 7.

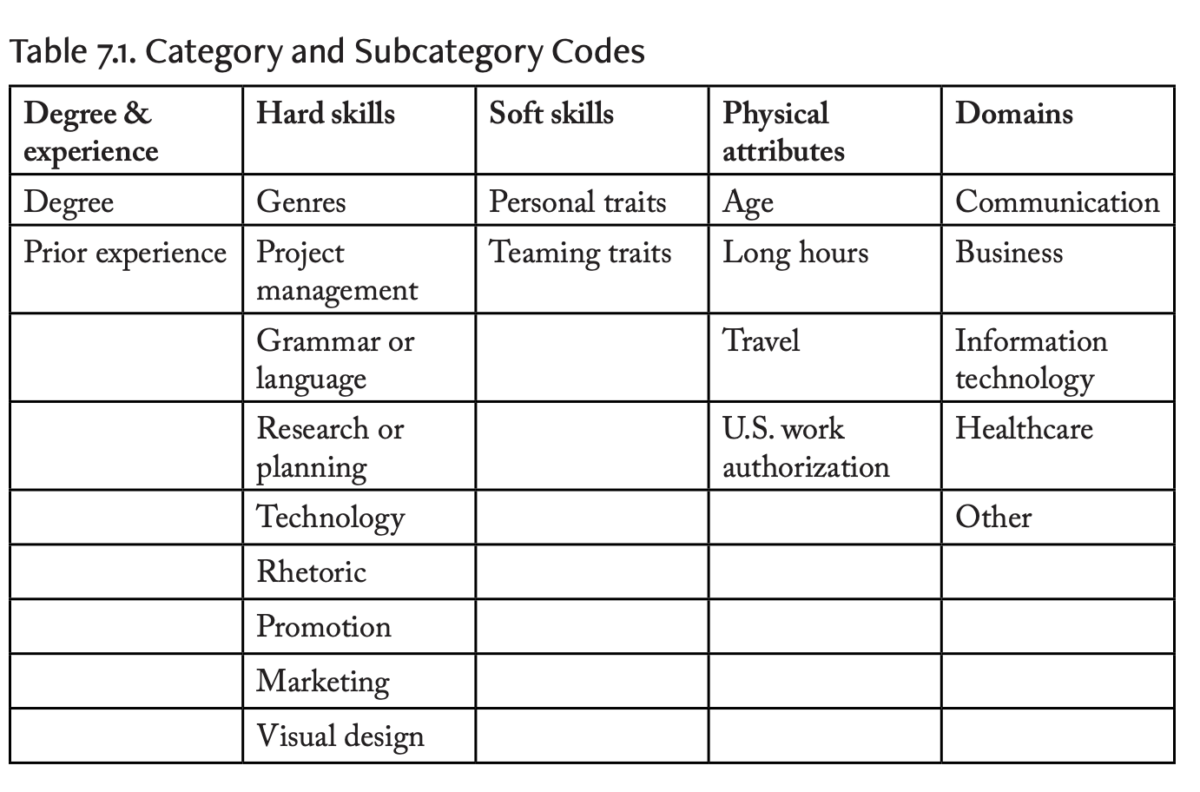

- Assessment: You will earn an incomplete if you merely copy a table from someone else’s table, such as Table 7.1 below from “7. Entry-Level.” Your information visualization should reflect a synthesis of information across the assigned readings.

- Submission Instructions: Upload a url or attach a .pdf to Canvas for grading.

Source: “7. Entry-Level Professional Communicators in the Workplace: What Job Ads Tell Us.” Source Education for Life and Work p 31 Source: Education for Life and Work

Sunday, 1/14, Assignment Due – Visualization of Information from “Contract Grading.”

Readings

- Data Visualization – Information Visualization – The Art of Visualizing Meaning For Better Decision-Making

- Review of Best Practices in Data Visualization

Assignment Guidelines

The goal of this exercise is for you to visually summarize information from a source.

- Read

- Deliverables:

- Develop an information visualization that visualizes research results and/or theory on contract grading. Your visualization could address the challenges and limitations of contract grading. Or, it could illustrate the benefits researchers have found with contract grading.

- Remember that if you use bullets or numbered lists, you want to follow Parallelism, Parallel Structure, Parallel Construction

- Length: 1 page, 200 to 250 words.

- Citation: APA 7. Be sure to signal to the reader that you are quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing.

- Write a research summary: Summarize in your own words the story you aimed to communicate in your information visualization.

- Develop an information visualization that visualizes research results and/or theory on contract grading. Your visualization could address the challenges and limitations of contract grading. Or, it could illustrate the benefits researchers have found with contract grading.

- Submission Instructions: Upload to Canvas a copy of your research summary and visualization in .pdf. You may also upload a url where I can access your visualization online.

Week 2, 1/15 to 01/21 – Introduction to Research Methods

Source

DasBender, Gita, et al. (2023). Contract Grading and the Development of an Efficacious Writerly Habitus. Journal of Writing Assessment, 16(1). DOI: 10.5070/W4jwa.231

Wednesday, 1/17, Assignment Due – Summary & Critique of Research Methods

The goal of this exercise is for you to summarize and critique the research methods employed by DasBender, G., et al. (2023) in their study “Contract Grading and the Development of an Efficacious Writerly Habitus.”

Assignment Guidelines

Readings

Tasks

- Review as needed:

- Engage, as a thought exercise, in a summary of “Contract Grading” from a methodological perspective

- Analyze the knowledge community this peer-reviewed, academic article invokes: practitioners, researchers, and theorists in writing studies – the academic field that studies writing, rhetoric, and composition.

- What can you tell about the values of this community based on the way the publishers of The Journal of Writing Assessment acknowledge their use of use peer-review, present DOIs for articles, and publish with a CC-BY 4.0 Creative Commons copyright? Notice their statement regarding equal coauthorship and commitment to open-access information. How does that inform your sense of ethos? How do members of this discourse community use diction and jargon? How would you use describe the tone of this discourse?

- Skip the Review of Literature and jump down to the Study Overview & Rationale.

- Evaluate the authority of the article by analyzing the research methods DasBender et al. used to investigate the efficacy of labor-based grading practices. Notice DasBender et al. report on the following data collection and data analysis methods:

- IRB and Ethical Matters independent variables

- Labor-Based Contract

- Unilateral Grading Contracts (assessment includes evaluations of quality)

- Different types of FYC sections

- Racial/ethnic and sex/genderself identifidations

- status as multilingual or first-generation-in-college

- investigators excluded data from sections for which there weren’t comparisons (labor-based or unilateral contracts.

- Data Analyzed:

- course grades

- numerical survey responses

- narrative summary responses

- Evaluate the authority of the article by analyzing the research methods DasBender et al. used to investigate the efficacy of labor-based grading practices. Notice DasBender et al. report on the following data collection and data analysis methods:

- Analyze the knowledge community this peer-reviewed, academic article invokes: practitioners, researchers, and theorists in writing studies – the academic field that studies writing, rhetoric, and composition.

- Deliverables

- Research Methods Summary: Write a summary of the research methods DasBender et al report on in their research study “Contract Grading.” Length: 250 to 500 words. In your summary provide the detail your readers need to understand and replicate the study (See What is RAD? – Replicable, Aggregable, Data-Supported Scholarship?)

- In a research summary, your readers expect you to

- provide the bibliographical information readers need to find the source. Cite “Contract Grading” in APA 7 format at the top of your document.

- succinctly explain the study’s contribution to peer-reviewed research.

- categorize the research as primarily as a contribution to scholarship — typically textual research methods, hermeneutical methods — or as a contribution to empirical knowledge – or what professionals might positivistic knowledge or scientific knowledge.

- use the vocabulary, diction and jargon appropriate for your audience. Whenever possible, practice brevity. . Use simple language

- engage in audience analysis

- In a research summary, your readers expect you to

- Research Methods Summary: Write a summary of the research methods DasBender et al report on in their research study “Contract Grading.” Length: 250 to 500 words. In your summary provide the detail your readers need to understand and replicate the study (See What is RAD? – Replicable, Aggregable, Data-Supported Scholarship?)

- Submission Instructions: Upload your summary and critique of research methods to Canvas.

Sunday, 1/21, Assignment Due — Academic Search Premier or JSTOR

The goal of this exercise is for you to engage in strategic searching of the “gated web” for peer-reviewed research on a topic of interest to you.

Tasks

- Use either Academic Search Premier or JSTOR to engage in strategic searching on a topic of interest to you. These databases and more are available at the Library Services, which is on MyUSF’s homepage.

- Engage in critical analysis of the article. Consider its accuracy, authority, currency, purpose, and relevance.

- Write an “evaluative summary” — a summary of a peer-reviewed article that interests you. In your summary of an article provide the detail your readers need to understand and replicate the study (See “What is RAD?“).

Suggestions:- Provide the bibliographical information your readers need to find the original source. Use APA 7

- When you introduce the source into your text, tell your readers about the source:

- Why is the source interesting? credible? authoritative?

- Who were the authors. Are they practitioners, researchers, or theorists? What were their qualifications?

- What was the purpose of this research study or article?

- How was the research study or article a contribution to knowledge?

- What methods did the investigators use?

- Why is the source interesting? credible? authoritative?

- Deliverables

- Upload your evaluative summary to Canvas in .pdf. Length: 200 to 250 words

- Upload an informal note to me that tells me about your search process. Length: 150 to 200 words

- What did you learn about Academic Search Premier or JSTOR?

- Did you engage serendipity in your search process? If so, how? If not, why not?

- How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Week 3, 01/22 to 01/28 – Rhetorical Analysis of the PTC Discipline

Wednesday, 1/24, Assignment Due – Rhetorical Analysis #1 – What Are the Discourse Practices of Professionals in the PTC Field?

The goal of this exercise is to ask you to engage in rhetorical analysis of journals published in professional and technical communication.

Assignment Guidelines

This exercise is based on the assumption that participants possess an understanding of the Information Literacy Frameworks as outlined by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), a division of the American Library Association. These frameworks are essential for writers, speakers, and knowledge workers in higher education. The ACRL Framework for Higher Education includes six key concepts:

- Authority is Constructed & Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information Has Value – Copyright & Writing

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as a Conversation – The Conversation of Humankind

- Searching as a Strategic Exploration

Context

Researchers identify research questions to investigate by

- engaging in strategic exploration

- engaging in serendipity

- reading peer-reviewed literature on a topic

- engaging in critical analysis of peer-reviewed articles published in authoritative sources.

- Researchers question the authority of what they read. Here authority refers to “expertise” as opposed to “power.” Authority is a quality that lends weight to an argument due to the expert’s research methods or personal and/or professional qualifications.

Tasks

- Carefully read Jason Tham’s List of Journals in PTC

- Engage in rhetorical analysis of two of these journals.

- Skim through the table of contents of articles published by two journals in PTC from Jason Tham’s list below. Look at articles published in two journals over a one-year period

- What are the scholarly conversations that are being discussed in these journals?

- What is the audience for the journal? Practitioners, Researchers, Theorists?

- Who is the publisher of the two journals?

- What is the authority of the publisher? Is the publisher a professional organization? a university? a non profit? a company?

- What are the qualifications of the authors of the journal articles?

- What are the scholarly conversations — the topics and research questions used by the authors of these articles?

- What research methodologies these authors employ?

- What are the citation practices of the authors? Do they use APA? MLA? Chicago?

- Do you notice if any of the journal articles have information visualizations?

- Write a memo to your instructor and peers that informs them about your thoughts regarding the discourse practices of members of the professional and technical writing community

- Length: 150-200 words (Please indicate the word count at the beginning of your document.)

- Objective: Provide a concise summary of your understanding of the Professional and Technical Communication (PTC) field, based on your analysis of articles from two selected PTC journals over the past year.

- Scope: Focus on articles published in two PTC journals within the last year.

- Analysis Goal: Conduct a rhetorical analysis to discern the underlying values, discourse practices, and epistemological assumptions evident in these journals. Consider the perspectives of the readers, authors, and publishers of the articles you examined.

- Summary: Your note should encapsulate key insights and inferences drawn from your analysis.

- Skim through the table of contents of articles published by two journals in PTC from Jason Tham’s list below. Look at articles published in two journals over a one-year period

Submission Guidelines: 2 Deliverables

- Upload a .pdf version of your rhetorical analysis to Canvas for grading

- Upload an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Jason Tham’s List of Journals in PTC

Journal of Business and Technical Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Theory driven; seems to balance qualitative and quantitative research

- Focus: Technical and business communication practices and pedagogy; discussions about training students to be professionals; some useful teaching strategies and cases

- Notes: Currently one of the top journals in technical communication; arguably most cited; has a strong tie to Iowa State’s professional communication program

Journal of Technical Writing and Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly less theoretical than JBTC and TCQ but still heavy academic-speak

- Focus: Trends and approaches in technical communication practices and research

- Notes: One of the oldest technical communication journals in the US

Technical Communication (Society for Technical Communication)

- Nature: Arguably more practical than JTWC, JBTC, TCQ, and IEEE Transactions; caters to STC’s professional audience… and it’s associated with the STC’s annual summit

- Focus: Emerging topics, methods, and practices in technical communication; content management, information architecture, and usability research

- Notes: It’s behind a paywall some university libraries may not even access; there is an online version of the journal called Technical Communication Online… but it’s not as prominent as the print journal; seems to have a strong association with Texas Tech’s technical communication program

Technical Communication Quarterly (Association for Teachers of Technical Writing) (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Theoretical + pedagogical

- Focus: Teaching methods and exemplary approaches to research; features many exemplary qualitative research cases

- Notes: Another top journal in technical communication; produces many award-winning pieces; associated with ATTW so it has a huge academic following… especially those who also attend the annual Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC)

IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication (Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers – Professional Communication Society)

- Nature: 50-50 theory and practice

- Focus: Engineering communication as professional communication; empirical research

- Notes: Another old journal that has a lot of history; seems to have a strong tie to the University of North Texas’s technical communication department

IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society (IEEE Society on Social Implications of Technology)

- Nature: 30% technical, 70% philosophical discussions about social technologies

- Focus: Computers science, CS education, technical design, social computing

- Notes: Good for interdisciplinary work, digital humanities, and digital education

Communication Design Quarterly (Association for Computing Machinery – Special Interest Group on Design of Communication)

- Nature: Theoretical, methodological

- Focus: Offers many accessible (comprehensible) research reports on design methods, research practices, teaching approaches, and industry trends

- Notes: Open access…yay! Recently pursued an “online first” model where articles are published on a rolling basis; it’s considered the second-tier journal in the academic circle but it’s surely becoming more popular among technical communication scholars

Journal of Usability Studies (User Experience Professionals Association)

- Nature: For academics, this is highly practical

- Focus: Empirical research; mostly quantitative

- Notes: Independent journal not associated with an academic institution

Behaviour and Information Technology (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Computer science emphasis… so, experimental + theoretical

- Focus: Human-computer interaction; information design, behavioral science

- Notes: This is a UK journal… provides a nice juxtaposition to US journals and perspectives

Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (SAGE)

- Nature: Similar to BIT, experimental and theoretical

- Focus: Puts emphasis on the human factors and ergonomics discipline; draws from psychology

- Notes: As shown in its name… it’s a journal for the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society

Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly more theoretical than Human Factors

- Focus: Theoretical discussions, experiments, and demonstrations

- Notes: Also an HFES journal

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies (Elsevier)

- Nature: Theoretical

- Focus: More interdisciplinary than EID and Human Factors

- Notes: May be one that technical communication researchers feel more comfortable publishing in even if they are not working directly in HCI or computer science fields

Human Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, philosophical

- Focus: Discusses technological futures and human-computer interaction

- Notes: It’s got less prestige compared to EID and Human Factors

Human Communication & Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, empirical

- Focus: Communication studies and social technologies

- Notes: It’s fairly new and doesn’t seem to publish multiple issues a year

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (International Communication Association) (Oxford)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative

- Focus: Social scientific approach to computer-based communication; media studies and politics; social media research

- Notes: Top journal for solid communication technologies research

International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development (IGI Global)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative; practical

- Focus: Social scientific approach to technology studies and professional communication; seems catered to practitioner audience

- Notes: Has an interdisciplinary feel to it; one or two special issues are of specific interest to technical communication design

Business and Professional Communication Quarterly (SAGE)

- Nature: Theoretical, pedagogical

- Focus: Workplace communication studies and teaching cases

- Notes: A journal of the Association for Business Communication (ABC); top tiered for business writing and communication research

International Journal of Business Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Practical, pedagogical, experimental

- Focus: Similar focus to BPCQ

- Notes: Also an ABC journal (I am not sure why there is this other journal)

Programmatic Perspectives (Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication)

- Nature: Programmatic, pedagogical

- Focus: Program and curriculum design; teaching issues; professional development of teachers

- Notes: Smaller journal… not sure how big is the readership but it’s got a good reputation

Xchanges: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Technical Communication, Rhetoric, and Writing across the Curriculum (Independent journal)

- Nature: Pedagogical, beginner research, experimental, teaching cases

- Focus: Technical communication, writing studies, rhet/comp, and everything in between!

- Notes: Open access journal with pretty good editorial support; provides mentorship to undergrad and graduate writing; multimedia friendly

RhetTech Undergraduate Journal (Independent journal)

- Nature: Beginner research, undergraduate research

- Focus: Writing studies, rhet/comp, technical communication

- Notes: Open access; print based (PDF) so not very multimedia-friendly

Sunday, 1/28, Assignment – What are the Discourse Practices of Subject Matter Experts in PTC?

The goal of this exercise is for you to continue learning about the PTC field while practicing rhetorical analysis of research and scholarship conducted by members of the PTC community.

Related Concepts

- Rhetorical Analysis

- Genre Analysis

- Discourse, Discourse Conventions, Discourse Moves

- Rhetorical Moves in Academic Writing

Tasks

- Select two additional journals in PTC to analyze

- Engage in analysis of two journals to learn about the discourse practices of subject matter experts in PTC. Analyze the articles published over the past year in two additional PTC journals. Identify the titles, major sections, use of references. What research questions or other purposes inform these studies? Note shared discourse conventions, such as a deductive structure, a clear statement of the research question or hypothesis, an abstract, a review of literature (identification of the problem), and other common rhetorical moves. Note discourse conventions, methodological conventions, and genre conventions of research studies in the PTC discipline. For example, is the literature review a separate section or is it synthesized into the statement of the problem, research question, or hypothesis?

- Write a 200-to-250-word memo to me and your peers that explains what you’ve learned about the discourse practices of subject matter experts in the PTC field, as represented by the four PTC journals you reviewed. Use APA 7 and a professional writing style.

- Submission Guidelines: 2 Deliverables. Note: Please write the word count on the top of each document.

- Upload to Canvas a .pdf version of your rhetorical analysis, 200 to 250 words

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Week 4, 1/29 to 2/4

Wednesday, 1/31, Assignment Due – Quote, Paraphrase, and Summary Exercise

The goal of this exercise is to write a summary that uses the discourse conventions of both workplace and academic writing (e.g., Quotation, Paraphrasing, Summary, and APA 7) to accurately inform your peers about the key findings of a BCG Study on AI and productivity in the workplace.

- Review, as needed, from Writing Commons:

- APA Summary

- Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

- Citation Conventions – What is the Role of Citation in Academic & Professional Writing?

- Citation Conventions – When Are Citations Required in Academic & Professional Writing?

- Citation – How to Connect Evidence to Your Claims

- Citation & Voice – How to Distinguish Your Ideas from Your Sources

- Paraphrasing – How to Paraphrase with Clarity & Concision

- Quotation – When & How to Use Quotes in Your Writing

- Summary – Learn How To Summarize Sources in Academic & Professional Writing

- Read these articles:

- How Generative AI Can Boost Highly Skilled Workers’ Productivity

This is a summary of a Boston Consulting Group research study. It’s published by MIT Sloan Management - How People Can Create—and Destroy—Value with Generative AI

This is an example of a professional research study conducted by Boston Consulting Group [Note the ways this study reflects the discourse practices of the PTC community. Note the use of visual design to bring focus to the key results.]

- How Generative AI Can Boost Highly Skilled Workers’ Productivity

- Writing for an audience that hasn’t had time to review the BCG study, write a 200-to-250-word research summary of the study’s highlights In what ways did the BCG study find that AI can help professionals be more productive? In what contexts did BCG find AI may impede critical thinking? How does the BCG study imagine AI being used in business? Be sure to paraphrase, quote and summarize from the BCG study using APA 7 format.

Submission Guidelines: 2 Deliverables. Note: Please write the word count on the top of each document.

- Upload to Canvas a .pdf version of your summary. You may also link out to a gdoc.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

- Submission Instructions: Upload your summary to the Canvas discussion board.

Sunday, 2/4, Optional Assignment Due – Project Proposal

The goal of this project is to give you the creative space to pursue a topic that you’re passionate about and explore it using a professional writing style.

If you wish to engage in the labor necessary to earn an A grade in this course, you need to complete one of the major assignments outlined above. Alternatively, you may pitch a research problem to solve a problem at work or develop an entreprenurial idea. The point here is I’m open to what you want to do. I want you to chase your passion on this project.

So that I may support your effort, I ask that you let me know which additional project you’re taking on to engage in the labor to earn an A grade.

Tasks

- Read Planning Technical & Professional Documents.

- Write a 250 to 500 word project proposal to me that updates me on the optional project you’ve decided to tackle.

- Identify the tasks you need to successfully complete the project.

- What strategic research do you need to conduct? Textual research? Interviews? Observations? Tests?

- What work have you completed on the project thus far?

- What is your schedule for completing the remaining tasks? (see due dates below)

- Create a Gannt chart or a table to illustrate your upcoming tasks and deadlines

Submission Instructions – 2 Deliverables. Note: Please write the word count on the top of each document.

- Upload the project proposal to Canvas. You may upload the document as a .pdf or provide a url that links out to a gdoc page.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI to write the project proposal. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Week 5, 02/05 to 02/11 – Research Ethics

Wednesday, 2/7, Assignment Due — NYT v. Open AI

The goal of this exercise is for you to consider the NYT’s charges that Open AI violated U.S. copyright laws.

Tasks

- Read

- Write a 150-200 word memo. Please indicate the word count at the beginning of your document. Inform your peers about the ethical and legal concerns associated with this lawsuit. Be sure to provide the details your readers need in order to understand why the NYT believes OpenAI violated U.S. copyright laws. Be sure to give the details and concrete language that readers need to understand why the NYT is suing OpenAI. Be sure to paraphrase, quote and summarize from the readings using APA 7 format.

Submission Instructions

- Upload your summary of the ethical and legal concerns raised by the NYT v. Open AI dispute.

- You may upload it as a .pdf or provide a url that links out to a gdoc page.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI to write your summary of the OpenAI vs NYT lawsuit. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process. Each week, try to use AI in a new way and then reflect on what you learned about writing, composing, and AI.

Sunday, 2/11, Assignment Due – Write a Methodological Description & Critique of a Research Study

The goal for this exercise is for you to accurately describe and critique the research methods used in a research study, “AI versus old-school“

Source Still Waters Lab <httpsblogstill waternetprojects> Tasks

- Read

- Engage in critique and analysis of this study: “AI versus old-school creativity: a 50-student, semester-long showdown”

- At the top of the page, provide the word count and reference the study in APA 7. Link to it.

- Use a professional writing style

- Introduce the study to your peers. Link to it. Provide your peers with the details they would need to replicate the study. For instance, how would you describe the methods the investigators used?

- Was it Applied Research or Basic Research?

- Was it a RAD-form of scholarship?

- What sort of research methods were used?

- Did the study raise any ethical concerns for you?

- If the study was reporting on original research (aka primary research, empirical research, or scientific research) did the investigators provide you with the information you needed to know that ethical research protocols were followed, as necessary professionally and legally?

- Did the investigators accurately and fairly reflect the

- How would you assess the ethos or authority of the investigators? Did the investigators make any interpretations, claims, or conclusions based on their research that in your opinion weren’t supported by the data?

- What were the key takeaways of the study? How does this study contribute to ongoing conversations and investigations into how higher education may need to response to the emergence of AI.

- Write for your peers a 200 to 250 word summary and methodological critique of “AI versus old-school.” Please indicate the word count at the beginning of your document. Please summarize the research study with the details investigators need to re-construct it (See RAD). Summarize the scholarly conversation and discourse community this study is responding to. What were the study’s key research questions, methods, results, interpretations?

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas your description and methodological critique of “AI versus old-school.”

- You may upload your submission as a .pdf or provide a url that links out to a gdoc page.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI to write your methodological critique. Length: 200 to 250 words. Please indicate the word count at the beginning of your document. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process. Be sure your response conforms to the expectations of a professional writing style.

Week 6, 02/12 to 02/18 – Introduction to Corpus Linguistics

For this and the next few assignments, we will be using this gdoc as our corpus: “Syllabi Policies for AI Generative Tools.” Compiled by Lance Eaton, an instructional designer, “Syllabi Policies” is a repository of instructors’ AI policy statements on their syllabi. Eaton has also made the resource available as a google spreadsheet.

Wednesday, 2/14, Assignment Due – Description of Faculty Members’ AI-Policy Statements

The aim of this assignment is to give you an opportunity to describe your perspective regarding the instructors’ AI policies.

Tasks

- Learn about corpus methods for analyzing large bodies of texts. For an excellent introduction to textual research methods and corpus methods, see

- Engage in analysis of “Syllabi Policies” – a compilation of instructors’ AI policies for their undergraduate and graduate courses.

- Below are some sample lines of analysis you might pursue to develop a detailed, honest description of professors’ reaction to the emergence of AI in higher education. For this assignment, you cannot possibly address all of these questions. Thus, it’s strategic to choose one or two of these questions to analyze for this assignment. Here are some different interpretive approaches you could use to describe the instructors’ AI policies.

- These faculty provide a range of acceptable and unacceptable uses of AI. What behaviors are encouraged or permitted? Which behaviors are prohibited?

- How can we discern the demographics of the contributors to “Syllabi Policies?”

- Do faculty who work in similar institutions — private universities, state universities, R1 universities, liberal arts colleges — share any perspectives? Or, can professors’ comments be sorted by discipline or subject to reveal any interesting results? How does filtering the information from the demographics of the educational institution (high school, community college, private college, university, etc.)

- By reviewing the course title, can you ascertain whether faculty from particular disciplines (e.g., the sciences, social sciences, humanities) tend to share perspectives?

- Are there any points a majority of faculty agree on?

- For instance do faculty agree “You may not use GenAI to produce an assignment in its entirety” (Noël – Boston College)

- What percentage of the faculty are entirely opposed to AI in the classroom?

- What percentage of the faculty explicitly said any use of AI is an instance of plagiarism and academic dishonesty?

- What percentage of faculty support the use of AI with an attribution on the part of the writer?

- How do professors ask students to attribute their use of AI? Do they provide specific citation conventions? For instance, do any of them point to the APA guidelines for citing AI? Are faculty concrete or vague about the policies they expect students to follow in the classroom?

- How do faculty describe the usefulness of AI during various stages of the writing process — prewriting, inventing, drafting, collaborating, researching, planning, organizing, designing, rereading, revising, editing, or proofreading.

- What percentage of faculty support the use of AI without any attribution?

- What penalties will students pay if they use AI and it has hallucinated — it has created false academic journals or publishing companies?

- What happens to students if they have cited work that is “fake” or offensive?

- How many of the authors explicitly mention academic integrity and ethics?

- Below are some sample lines of analysis you might pursue to develop a detailed, honest description of professors’ reaction to the emergence of AI in higher education. For this assignment, you cannot possibly address all of these questions. Thus, it’s strategic to choose one or two of these questions to analyze for this assignment. Here are some different interpretive approaches you could use to describe the instructors’ AI policies.

- Write a 200 to 250 word description of faculty members AI-policy statements. Share with your peers the shared commonalities and disparities you observed in the faculty members’ AI policy statements. Be as descriptive, honest, and accurate as possible.

Submission Instructions

- Upload your description to Canvas

- You may upload your submission as a .pdf or provide a url that links out to a gdoc page.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note to me that tells me about your use of AI to write the project proposal. Length: 150 to 200 words. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Sunday, 2/18, Assignment Due – Visualization of Corpus Data

Tasks

- To learn more about corpus analysis, review

- Read

- Reflect on the ways the goals of academe and the business community may diverge as AI becomes an important part of work — i.e., as businesses cut costs by eliminating jobs and maximizing AI efficiencies.

- Look for evidence (see exemplification) to support your claims. When you cite authors in the syllabi, do so by name, just as you would if citing an author in an academic article. Be careful to be honest and accurate. Don’t, e.g. say that the AI policy you are discussing is a particular university’s policy.

- Choose a visualization tool to create a data visualization of results you have inferred from analyzing the “Syllabi Policies” corpus. In your visualization contrast the values of academe with those of business or contrast the differing opinions faculty have with one another regarding the appropriateness of students co-authoring works with AI.

- Write a 200 to 250 word description of faculty members AI-policy statements. Share with your peers the shared commonalities and disparities you observed in the faculty members’ AI policy statements. Be as descriptive, honest, and accurate as possible.

Submission Instructions

- Upload your visualization to Canvas. You may share it by providing a link to it online. You may provide a screenshot of it.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note (150 to 200 words) to me that (1) tells me about how you used AI to compose your visualization; (2) explains which visualization tool you used and why you chose it; (3) explains your design choices for your visuaization. Adopt a professional writing style. How did you use AI? Explain how you used it and what you learned about integrating it into your writing process.

Week 7, 2/19 to 02/25 –

The aim of this exercise is (1) for you to be introduced to corpus analysis methods and (2) to to ascertain whether the corpus tool gave you any insights regarding patterns in the corpus — shared values, polices, mindsets across professor’s AI policy statements.

Sunday, 2/21, Assignment Due – Experiment with Corpus Analysis

This assignment asks you to learn something new — to try a tool, a corpus analysis tool — to look at that corpus of ai policy statements in a new way. Remember as well last week’s readings on corpus analysis:

The tools and methods writers use are constantly evolving. It’s good to be quick at learning new tools

Text Analysis Tools

Source: this list below is informed by Anthony Sanchez’s list of tools. Sanchez is a librarian at the University of Arizona.

- AntConc

- Voyant Tools

- TagCrowd

- NGram Analyzer

- Voyant

- The easiest to use web text analysis tool. Voyant is free and allows users to upload or paste text. The program will automatically determine word frequencies and colocates and display them graphically.

- MALLET

- MALLET (MAchine Learning for LanguagE Toolkit) is a collection of tools that facilitate document classification, sequence tagging, and topic modeling. There is also an add-on toolkit (Graphical Models in MALLET) for visualization.

- The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group Software

- The Stanford NLP Group makes some of our Natural Language Processing software available to everyone! We provide statistical NLP, deep learning NLP, and rule-based NLP tools for major computational linguistics problems, which can be incorporated into applications with human language technology needs. These packages are widely used in industry, academia, and government.

- Taporware

- This collection of text analysis tools hosted by the University of Alberta provides XML, HTML, and plain text analysis. Upload documents to extract common words, determine colocates, separate HTML tags, and extract XML tagged information.

- Topic Modeling Tool

- This is a simple free tool that allows users to topic model texts using MALLET, but with an easy-to-use graphical user interface.

- WordSeer

- WordSeer is a collection of text analysis tools targeted at humanities scholars that includes side-by-side comparison, grammatical search, and document/sentence/word-set features.

- JSTOR Data for Research

- Data for Research is a free data mining tool for journal content on JSTOR, available to the public. DfR provides the ability to obtain data sets via bulk downloads, and includes a powerful faceted search interface, online viewing of document-level data, downloadable datasets (including word frequencies, citations, key terms, and ngrams).

- Wordle

- Make a word clouds from your own text.

- TAPoR

- TAPoR is a gateway to tools for sophisticated analysis and retrieval, along with representative texts for experimentation.

Personally, I’m not expert on those tools, though I have played around with them. I’ve published a couple of articles that used corpus linguistic methods. My part in those coauthorships was securing IRB approvals and writing, the writing protoco and then the results:

- Dixon, Z., & Moxley, J. (2013). Everything is illuminated: What big data can tell us about teacher commentary. Assessing Writing, 18(4), 241-256.

- Durrant, P., Moxley, J. & McCallum, L (2019). Vocabulary Sophistication in Freshman Composition Assignments. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 24:1, pp. 36-66. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.17052.dur

Being able to analyze a corpus is foundational to work in AI.

The takeaway here is that corpus linguistics has become a burgeoning area of interest for researchers who want to study the emergence of new communication technologies and explore their effects on human communication creativity, communication, and subsequent artifacts — oceans and oceas of texts, movies, web pages, books, articles, magazines, reference books–and more: the conversation of human kind.

For those completing the labor to earn an A grade, this is a perfect time to reflect on the tools you use and their helpfulness.

Tasks

- Pull some data (copy/paste) from Syllabi Policies and then use a corpus tool to analyze the sample data.

- Describe your research analysis methods.

- Described which part of the corpus you studied — the whole thing or parts related to a particular research question?

- Write a 500-word memo to your peers that explains your methods and findings. Include visualizations of findings. Be sure to inform your peers about which tool you used.

- Write a 150-to-200-word informal note to me that tells me which corpus tools you used to study the corpus. Tell me about the different corpus tools you tried. Why did you choose the tool you did? Did using the corpus tool give you any new insights into the corpus? Did you gain any insights into some aspect of the corpus? Also be sure to explain how you used AI and what you learned about integrating AI into your writing process.

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas the memo you wrote to your peers to share your findings

- You may upload it as a .pdf or provide a url that links out to a gdoc page.

- Upload to Canvas an informal note (150 to 200 words) to me that (1) explains about your experience using the tool and (2) reflects on your use of AI.

Week 8, 02/26 to 03/03 – No Assignments Are Due This Week

Dear Students, Please note that I will be unavailable this week. If you are putting the labor in to earn an A in this course, this would be a good week to get some work done on that project.

Week 9, 3/4 to 3/10

Note: Spring Midterm Grading Ends

Wednesday, 3/6, Assignment Due – Problem Definition Memo

Ok! Now — following weeks of discussion and a group exercises, it’s your time to summarize the corpus with authority. Consider this the Super Bowl!

Ideally, your goal here is to be accurate, truthful, comprehensive — and insightful. Your goal is to describe the problem space that teachers and students find themselves in thanks to the rise of AI. Beyond other students and teachesr, consider your audience to be the broader public–people who are curious about how higher education is responding to tools such as ChatGPT

Please use words — a professional writing style and at least one visual but multiple visualizations are welcome.

In terms of genre, you may write this as a memo or article.

Required Word Length: 500 words. Place word count on top of page.

Important Note: You will not receive credit for this work unless all requirements are completed.

Suggested Tasks

- As a first step, please review once again Eaton’s Syllabi Policies for AI Work. Carefully analyze the range of policy statements faculty have authored to govern the use of AI in their classrooms.

- Review — for inspiration — some of the visualizations you and your classmates have designed (see course sandbox)

- Reflect on multiple lines of analysis:

- How can we discern the demographics of the contributors to “Syllabi Policies?”

- Do faculty who work in similar institutions — private universities, state universities, R1 universities, liberal arts colleges — share any perspectives? Or, can professors’ comments be sorted by discipline or subject to reveal any interesting results?

- By reviewing the course title, can you ascertain whether faculty from particular disciplines (e.g., the sciences, social sciences, humanities) tend to share perspectives?

- Are there any points a majority of faculty agree on?

- For instance do faculty agree “You may not use GenAI to produce an assignment in its entirety” (Noël – Boston College)

- What percentage of the faculty are entirely opposed to AI in the classroom?

- What percentage of the faculty explicitly said any use of AI is an instance of plagiarism and academic dishonesty?

- What percentage of faculty support the use of AI with an attribution on the part of the writer?

- How do professors ask students to attribute their use of AI? Do they provide specific citation conventions? For instance, do any of them point to the APA guidelines for citing AI? Are faculty concrete or vague about the policies they expect students to follow in the classroom?

- How do faculty describe the usefulness of AI during various stages of the writing process — prewriting, inventing, drafting, collaborating, researching, planning, organizing, designing, rereading, revising, editing, or proofreading.What percentage of faculty support the use of AI without any attribution?

- What penalties will students pay if they use AI and it has hallucinated — it has created false academic journals or publishing companies?

- How many of the authors explicitly mention academic integrity and ethics?

- How can we discern the demographics of the contributors to “Syllabi Policies?”

How To Cite from the Corpus

- Get the Author Name from the Contributor field

- Provide Name of Course as if it’s the title

- List the Name of the Institution as the Publisher

Submission Instructions

- Upload your problem-definition memo/article to Canvas

- Upload an informal note to your me regarding how you experimented with AI to complete this project.

Friday, 3/8, Optional Assignment Due – Project Update -2

- For those of you who are engaging in the labor to earn an A in this course, provide a progress report. Show me a copy of what you’ve completed thus far. Tell me what you need to do next. Make a Ghent chart or table to illustrate the work you need to complete in order to submit the assignment on time.

Week 10, 03/11 to 03/17 – Spring Break Week

Week 11, 03/18 to 03/24

Wednesday, 3/20, Assignment Due – Collaborative Survey

Tasks

- Read Survey Research and also Surveys on p.5 of Chapter 5

- Contribute in a collaborative effort to coauthor two surveys:

After reading about surveys, propose some demographic questions, multiple choice questions, and open-ended questions on both surveys.

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas an informal note (150 to 200 words) to me that

- tells me how you contributed to the student and teacher surveys. Be specific and honest. How did you help develop the surveys?

Sunday, 3/24, Assignment Due – Interview – 1

Tasks

- Read

- Working With People, Try This

- Writer Identity, Literacy, and Collaboration: 20 Technical Communication Leaders in 2020

- Interview a professor, a student, or a business person on how they are using AI in their academic or professional writing.

- Write a summary of the interviewers’ thoughts on the role of AI in higher education

- contribute to the student and teacher surveys.

Please note that I’m looking for a volunteer to link to build the student and teacher surveys in a survey tool. ASAP, I’d like to launch the surveys. For this work, I will erase a missing assignment. Because there are two surveys, I need two volunteers, at least.

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas Interview 1

- Provide a url that links out to a gdoc page that contains your interview…

- Upload to Canvas an informal note (150 to 200 words) to me that

- tells me what you learned about conducting interviews or listening as a result of the readings or assignment work

- explains how you used AI and what you learned about integrating AI into your writing process.

Week 12, 3/25 to 03/31

Note: Spring last day to withdraw; no refund & no academic penalty.

Wednesday, 3/27, Assignment Due – Interview – 2

Assignment Guidelines

- Review

- Working With People, Try This

- Interview a professor, student, or business leader on the impact of AI on higher education (e.g., AI and the future of communication) or business (marketing, design, and all other forms of work). Write, using gdocs, a summary of the interviewers’ thoughts on how AI is influencing their composing practices, business practices, and the future of academe/work. Avoid a question/answer format because that may create choppiness in tone and a loss of stylistic unity. Instead, digest what you’ve learned, ascertain key, interesting points, and they reveal them for the reader with sufficient detail that they can follow and learn from you.

- The interview can be anonymous, yet if so create an image; if not, use the real image. A lack of a pic will earn an “incomplete.”

- If you want, you can write up the interview from their perspective, as if you are them. If you choose this option, just put a line in the page separating the bio and pic from the story. IOWs, if you like, you may write up the interview from the persona and point of view of the person you interviewed. Or, you may narrate the story from your perspective–that of a researcher who is curious to learn more about the effects of AI on the future.

- Remember how when we were talking about info lit, and I explained the importance of introducing the authority of your textual sources? Well, that still makes sense. At the top of the page, you want to introduce the expert, give their bio and expertise on the topic.

- Be sure to provide specifics about how the interviewees uses AI now. Note, if they don’t know anything about AI, move on. It’s a waste of time not to interview someone w/ some expertise on AI. Find someone who has used AI! Explore their comments as they come up.

- Minimum word count: 400 words.

- Use a professional writing style. Interviews that are one paragraph will not receive a “complete.”

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas a link to your interview at gDocs. To receive credit, share the URL that permits editing. Note: Submissions that aren’t in “edit view” will not receive credit, nor will their be opportunities for revision.

4/31, Sunday

Nothing is Due

Week 13, 4/01 to 4/07

Wednesday, 4/03, Optional Assignment Due – Project Update #3

For those of you who are engaging in the labor to earn an A in this course, provide me with a progress report. Show me a copy of what you’ve completed thus far. Tell me what you need to do next. Make a Ghent chart or a table to illustrate the work you need to complete in order to submit the assignment on time.

Sunday, 4/07, Assignment Due

- Final Revisions to the Survey

Submission Instructions

- Upload to Canvas a screenshot that demonstrates you completed the online course evaluation.

Week 14, 4/08 to 4/14

Wednesday, 4/10, Assignment Due – Recommended AI Policies for Students

Based on the research you have completed in this course, write an AI Policy Statement for students. Remember, your goal in this assignment is not to elaborate on your process or personal opinions. Instead, keep the focus on the policies you recommend. Avoid first person. Adopt a professional writing style; remember, this includes incorporating visualizations, a. Use APA 7 for citations.

Submission Instructions

Upload to Canvas a link to your AI Policies for Students at gdocs; use edit view.

Friday, 4/13 – Peer Review Exercise

Provide a Link to Your Revised AI Policies for Students at the Course Sandbox. Be sure the gdoc link you provide permits edit access. Next, make at least 2 comments on peers’ drafts of their AI Policy Statement for Students. Then upload a note to me explaining whose policy statements you reviewed. Please note: if you received a “complete” on your student policies, feel free to upload a rough version of your teacher policies.

Sunday, 4/14, Revisions to Recommended AI Policies for Students

If you received an “incomplete” or no grade, upload your revision to the drop box for “Recommend AI Policies Statements for Students. I’ve changed the due date there at canvas for Sunday night. If you received a complete for student policy statement, pls upload a draft of your policy guidelines for teachers.

Sunday, 4/21, Assignment Due – Recommended AI Guidelines for Teachers

Based on the research you have completed thus far, write guidelines for teachers that they can publish on their syllabi. Remember, your goal in this assignment is not to elaborate on your process or personal opinions. Instead, keep the focus on the policies you recommend. Avoid first person. Adopt a professional writing style. Use APA 7 for citations.

Submission Instructions

Upload to Canvas a link to your AI Policies for Students at gdocs; use edit view.

Week 15, 04/15 to 04/21

At USF, Test Free week is 4/20 to 4/26

Sunday 4/24, Assignment Due – Final Draft for Optional Assignment

Submission Instructions

Upload to Canvas a .pdf version of your optional assignment or provide a link to it at gdocs.

Friday, 4/26, Grade Computation

Review the syllabus policies for labor-based grading. Review your grade-book assignments scores. Then write a one-page memo to me summarizing your grade for the course. Also, if you don’t mind, add a note at the bottom of your grade computation that gives me feedback on the course, especially our labor-based approach. As you know, in this class I limited the weekly work, making them small assignments, with hopes that would free you up to follow your passion. The end result, I believe, for many of you has been fantastic. I hope my intuition is right here but if not let me know. I do have ideas for improving this course next time, but I’m also open to yours.