Synonymous Terms

Textual research methods is also known as scholarship. Other synonyms include

- Textual Analysis

- Scholarly Research

- Academic Research

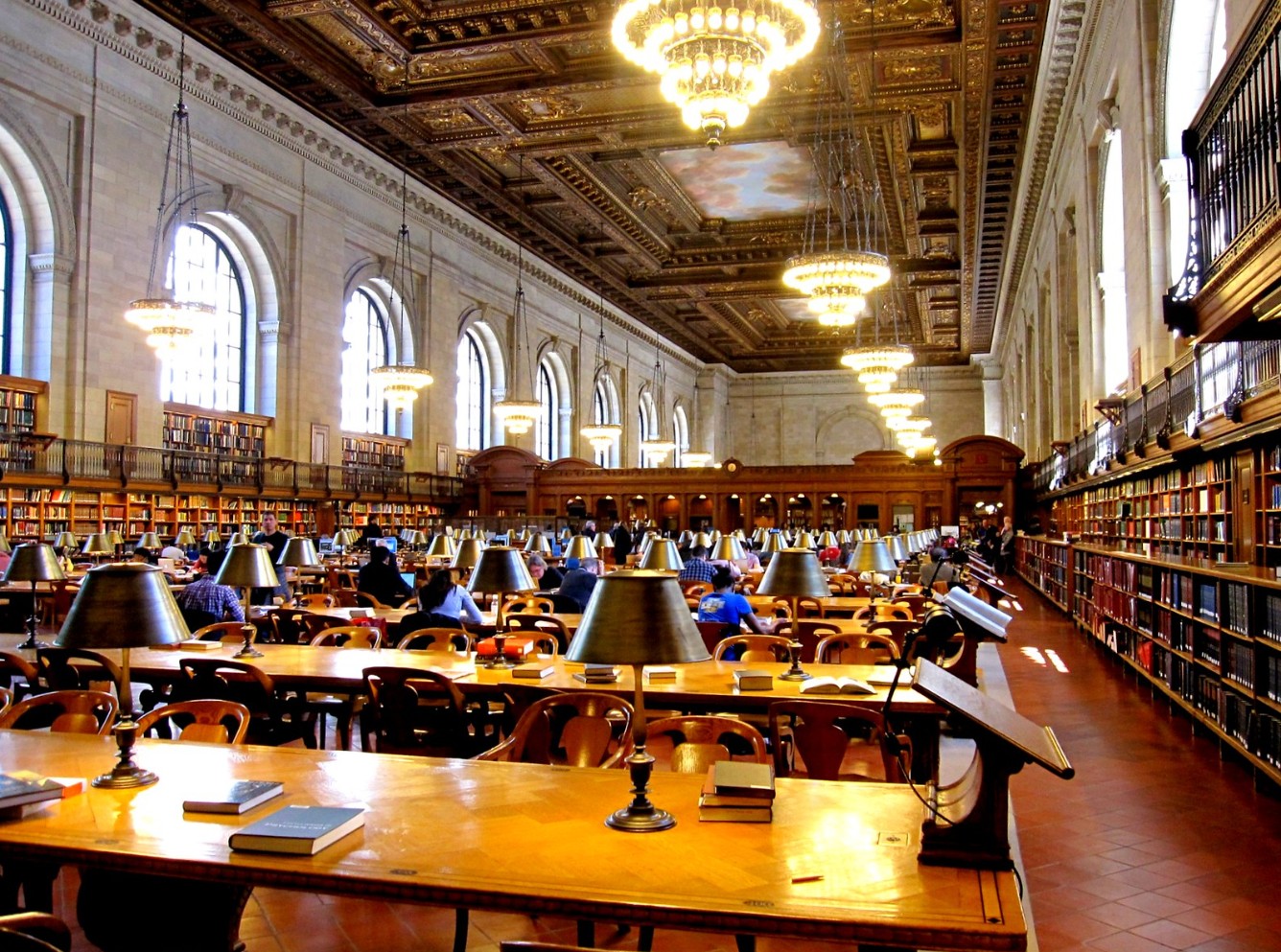

- Library Research

- Desk Research

- Secondary Research.

Related Concepts: Dialectic; Hermeneutics; Semiotics; Text & Intertextuality

What are textual research methods?

Textual research methods refers to the methods scholars use to interpret texts, to assess knowledge claims, and to develop new knowledge. Any time you are interpreting, learning from, describing, and discussing texts, you are engaging in textual research.

Texts are so ubiquitous in our modern lives that we often engage in textual research informally without thinking consciously about our actions as a form of textual research. For instance, we may

- use a GPS system to navigate a trip

- search the web for pricing and reviews

- read nonverbal language and back channel discourse.

Even simple literacy tasks like looking up how to pay a parking ticket or investigate travel options requires some mastery of textual methods.

There are many different ways to conduct textual research. Academic disciplines and professions have unique approaches to engaging in textual research. For instance, lawyers may engage in textual research by surveying applicable laws, policies, and precedents. In contrast, a clinical psychologist might read peer-reviewed research on personality constructs. Thus, it’s helpful to think of textual research as a suite of practices, a range of options, that are deployed based on the rhetorical situation.

Formal textual research methods are taught in high school, college, and professional workplace settings. At a minimum, teachers in school settings—from middle schools, high schools, to colleges—train students to write with sources (e.g., how to summarize, paraphrase, and quote). Masters and doctoral programs provide discipline-specific training in research methods. As an example, consider legal training in the U.S.: following undergraduate studies, law students enroll in three additional years of training that focus on how to interpret texts from a legal perspective and engage in legal reasoning.

To help develop our competencies as textual researchers, teachers in school settings ask students to

- read/analyze a text to learn and think about existing knowledge, knowledge claims, research questions, hypotheses, theses, information

- speculate and engage in reasoned debate with others about texts and textual interpretations

- share our subjective readings of others’ texts (reader response)

- explore how interpretations of texts are historically and culturally situated and how those interpretations change over time, place, and cultures

- engage in intertextual analysis—e.g., analyze how thinking about a particular topic and knowledge claim evolves over time

- use theory (e.g., marxism, gender studies, critical race theory)

- to inform an interpretation of a text

- to understand what a text and past interpretations of a text say about humanity and culture

- develop knowledge and knowledge claims by composing in response to other texts.

Hermeneutics

| Clarification: Primary Texts vs. Secondary Texts Some researchers, particularly archivists, make a distinction between primary and secondary texts: Primary Texts A primary text is an original text by an author, such as a memoir, autobiography, or journal. Secondary Texts A secondary text is a text that summarizes, paraphrases and cites other texts. Examples of secondary texts are journal articles, reports, or proposals. |

Textual Research Methods are informed by hermeneutics, a philosophy of interpretation and understanding, and the concept of a hermeneutic circle—i.e., the idea that interpretation is an integrative, reiterative process informed by

- multiple readings/interpretations

- readings change over time in response to the idiosyncrasies of readers, changes in culture and media

- the historical context of the document

- the author’s and reader’s relationship to the historical context.

/Hermeneutic%20cycle.jpg)

Related Topics

Textual Research Methods & Empirical Research Methods

Textual Research Methods may play a major or minor role in how a text is developed:

- an author may use solely textual methods to develop a text. For example, the author may review peer-reviewed publications and compose an annotated bibliography or review of literature

- an author may rely primarily on empirical methods (e.g., qualitative and quantitative research) and only conduct textual research during the early stages of research, when trying to define and contextualize the research question, hypothesis, and methods.

Textual Research Methods & Information Literacy

Textual Research Methods are informed by information literacy practices. People can make informed interpretations when they have access to information and can assess the accuracy, authority, currency, purpose, and relevance of a text.

| Information Literacy | Your perspective, your ability to interpret texts, is shaped by your ability to locate, read, and assess texts. |

Textual Research Methods & Mindset

Textual Research Methods are also informed by the writer’s mindset: being curious and open to information, especially when it threatens your deeply held values and beliefs, requires intellectual openness, self-regulation, professionalism, and persistence.

| Growth Mindset | Are you a curious or close-minded person? Can you listen to and seriously analyze opposing points of view? |

| Intellectual Openness | Are you open to information? |

| Metacognition & Self-Regulation | How’s your self talk? Do you coach yourself to be curious? |

| Professionalism & Work Ethic | Do you have the grit necessary to do the work? |

| Resilience | When you discover the information you had was wrong, what do you do? Are you able to work your ideas through the necessary processes (see Composition) |

Textual Research Methods & Writing with Sources

Textual Research requires some mastery of conventions governing Writing with Sources, particularly the practices surrounding attribution: summarizing, paraphrasing, and citing secondary sources.

| Writing with Sources | To understand any given text, you need to understand conventions for Integrate Textual Evidence (Quotes, Paraphrases, Summaries) |

Textual Research Methods are informed by other competencies, especially

- hermeneutics

- Information Literacy, especially scholarship as a conversation;

- Attribution, Citation, & References

- Rhetorical Reasoning, especially Logos, Reasoning; Rhetorical Stance; Rhetorical Knowledge

- Flow: Integrate Textual Evidence (Quotes, Paraphrases, Summaries).