Literacy Definition

Literacy refers to, or functions as,

- the ability to read and write in home, school, workplace, and public settings

- an amalgam of competencies, skills, knowledge, and dispositions related to acts of interpretation, communication, or competency

- a commodity

- a technology, a toolset, that

- empowers people to develop their personal, social, and economic power

- empowers literate cultures to develop new ideas and methods, including science, social science, humanities, engineering, and arts

- a measure of educational attainment and audience awareness.

Related Concepts: Academic Writing Prose Style; Critical Literacy; Information Literacy; Intellectual Openness; Professional Writing Prose Style; Rhetoric & Apparatus Theory; Semiotics: Sign, Signifier, Signified; Writing Process

What is Literacy? – Guide to Literacy in 2023

Definitions of literacy are constantly changing as cultures and technologies evolve–and as our understanding of reading and writing becomes more nuanced. Throughout much of human history, literacy referred simply to a person’s ability to read and write alphabetical texts. Around 3400 BC in Sumer (in modern day Iraq) you were literate if you could write in Sumerian on a clay tablet to record agricultural matters and business contracts. In the Middle Ages you were considered literate if you could sign your name with an X to symbolize “In Christ’s name, it’s true/I assert.” Later on, you were considered literate if you could read a bus schedule or a daily newspaper.

In more recent times, literacy has come to refer to

- any act of symbolic thinking (e.g., visual language, nonverbal language, or musical language) to communicate

- any competency. For instance, someone with sports knowledge could be said to have sports literacy. Or someone with knowledge of medical discourse might be described as scientifically literate.

In some discourse communities in 2023, you wouldn’t be considered literate if you couldn’t write computer code, create data visualizations, publish a podcast, or design an iPhone app. In workplace writing, as communication has become more visual and interactive, basic literacy may be defined as knowledge of the principles of design or universal design or even page design and scannability. In settings such as college-level courses, basic literacy may refer to the ability to manipulate photos, subscribe to and publish podcasts, data walk content across digital platforms, and publish content online via various digital tools, such as WordPress, Wiki, Instagram, or Tik Tok. As an example of audience awareness and changing literacy standards, consider, e.g., the following billboard that was posted by Electronic Arts to advertise job vacancies for programmers. In computer code, it reads “Now Hiring!” (Prensky 2008).

Thanks to advances in human knowledge, new writing spaces (e.g., clay or stone tablets, papyrus, paper, email, text messages, social media) are constantly evolving–and challenging existing assumptions about the best ways to read and write. These writing spaces along with new writing tools (e.g., fingers, quills, pencils, pens, keyboards, stylus, mouse, ChatGPT) have affordances and constraints that profoundly influence whether they replace existing technologies or whether they create new means of creative expression. When writing spaces and writing tools — the apparatus of writing — make a composing process easier, those tools are likely to be widely adopted. Note, for instance, how the internet’s affordance of permitting a single individual to communicate to a massive global audience has transformed authorship, copyright, politics, economics, culture, and intellectual property standards.

New writing spaces and writing tools are constantly redefining

- what it means to be literate

- what writers or speakers say, the evidence they present, and how they organize their content

- their research methodologies along with the epistemological assumptions about what constitutes a valid knowledge claim

- the medium of expression (e.g., alphabetical language; visual language; nonverbal language)

- their composing process (aka creative process).

- what writers or speakers say, the evidence they present, and how they organize their content

1. Literacy Refers to the Ability To Read and Write

Traditionally, the term literacy refers to humanity’s unique capability to read and write–and to engage in acts of symbolic thought. Between 16 and 24 months children are capable of associating words and symbols with concrete objects. For instance, when reading a children’s book, children may point to a familiar object such as a picture of a dog and say “dog” (“Symbolic Thought” 2012).

As humanity has developed new tools for expression (e.g., the print press, the internet, social media, AI – Artificial Intelligence), we have also developed more nuanced ways of defining literacy–new ways of conceptualizing reading and writing

Semiotics, an interdisciplinary academic field that investigates how people convey meaning to one another, conceptualizes reading to be an act of signification. In this model, meaning is composed of (1) a signifier –i.e., a word or symbol or something that conveys meaning to others — and (2) a signified–i.e., the underlying meaning associated with a sign. In other words, meaning is — a sign -which is any word, symbol, visualization or thing that can be interpreted to mean something.

In this definition of literacy, meaning-making is a social process: To communicate, writers and readers use signs that are socially shared among members of a discourse community. For communication to be successful, thus, the reader and the writer must share an understanding of what the Semiotics: Sign, Signifier, Signified means. In other words, writers and readers constitute a discourse community, a shared interpretative network. People are inculcated into the discourse practices of a community by reading, by communicating wit h others in the discourse community and through schooling–enculturation: Informally, they read the works of other community members, the archive, and learn over time who quotes whom–what the canon is.

During school, students are introduced to the expectations of discourse communities, particularly as they learn about the discourse practices of the academic and workplace writers. For instance, in the U.S. students learn the conventions of Standard Written English, including formal instruction in grammar, mechanics, and style–especially The Elements of Style. In higher education coursework, students enrolled in first-year writing courses across colleges and universities are trained to adopt an academic writing prose style. They are introduced to academic genres (e.g., an annotated bibliography or an argument), information literacy perspectives & practices, and citation practices. From reading, talks with others in a discourse community, and from their own experiences receiving critiques from others, they learn to share expectations about common patterns for genre, diction, grammar, mechanics, sentence structure, media–and more. In turn, students enrolled in workplace writing courses are introduced to the shared expectations of a professional writing prose style for business contexts. Broadly speaking, all of these discourse conventions constitute signs than can be interpreted by members of a discourse community.

2. Literacy Refers to a Synthesis of Cognitive, Interpersonal, and Intrapersonal Competencies

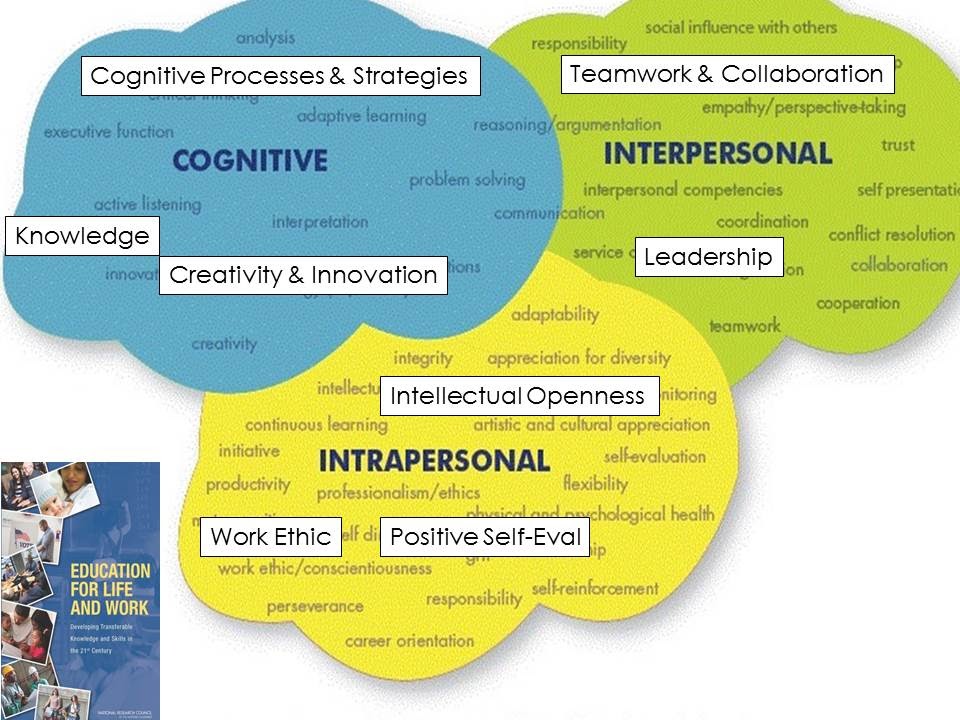

Literacy, as defined by the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) community is an amalgam of many competencies, skills, knowledge, and dispositions. In Education for Life and Work (2012), The National Research Council theorizes that all of the competencies involved in acts of communication coalesce under three foundational knowledge domains:

Notice in their depiction of these knowledge domains below that the National Research Council places communication, reasoning, and problem solving at the center of their conceptual illustration. In other words, the STEM community defines literacy as literacy a complex, symbolic process that is dependent on numerous interdependent competencies.

3. Literacy Refers to a Commodity

Literacy functions as a commodity: the ability to read and write, to engage in symbolic thinking, may be exchanged for money, goods, services, opportunities, and jobs. Mastery of specialized literacies — such as digital literacy, visual literacy, design literacy, financial literacy, health literacy — can be particularly profitable.

Moreover, ideas, concepts, inventions, original stories are all forms of intellectual property that are protected by copyright. Information has value.

Each year, NACE (The National Association of Colleges and Employers) surveys employers regarding their hiring plans and desires. Year after year, communication and critical thinking are the most highly sought after competencies. In 2022, for instance, 98.5% of the employers surveyed believed communication competencies were needed for career readiness, yet employers believed only 54.3% of college graduates were suitably prepared to communicate well in the workplace.

4. Literacy Refers to a Technology, a Toolset

In Writing Studies (and the broader education community) literacy is perceived to

- empower people to develop their personal, social, and economic power

- empower literate cultures to develop new ideas and research methods, including science, social science, humanities, engineering, and arts–and more.

Literacy Empowers People to Develop their Personal, Social, and Economic Power

Personal Power

Literacy provides agency. Strong communication skills will enable you to fight for changes you deem important and help you develop your goals and personal mission. Writing (and communication in general) enables you to articulate the need for change and action. Informing, persuading, and entertaining other people about your thoughts and insights enables you to provoke changes you deem important.

Literacy facilitates your personal development in meaningful ways. Engaging in writing about your goals can help you determine

- who you are

- who you will be

- develop awareness of others–different cultures, historical periods–and more

- affirm a growth mindset, take authority and ownership of your life

- how you can

- think independently and be an agent for change

- make the world a better place.

When you write something down on a page, you are no longer as slave to memory. Literacy empowers reflection, self regulation, and metacognition. By transforming your thoughts into text, you create an opportunity to return to that thought and reflect on it. This affordance of writing to help you record a thought for later reflection frees you from the tyranny of a moment-by-moment existence.

Writing from our hearts, sharing our experiences, can be important to our personal happiness. You can keep a journal to reflect on your writing processes, obstacles, and ambitions. When you read the work of other people who have different values, experiences, religions, and world views, your own knowledge and perspective may evolve. While conducting research for writing, you are likely to come across ideas, places, and concepts that you otherwise might not consider. While collaborating on documents, you may obtain insights from your co-authors regarding your strengths and weakness as a researcher, writer, and collaborator.

Social Power – Cultural Power

From a personal-social perspective, writing enables individuals to forge connections with family and friends as well as people we may not otherwise meet in face-to-face situations. Via handwritten notes to posts on social media, writing affords the possibility of connecting with friends and sharing insights and aspirations. Our writing can create rich social networks that give us a sense of meaning and connectedness.

From a nation-state perspective, literacy is an important measure of a country’s competitiveness, and a signal of the health of its people and the quality of its educational systems. Not surprisingly, nations are eager to measure literacy within their borders and across nation states.

- PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) is a worldwide assessment of the mathematical, science, and reading competencies of 15 year olds conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 2018, the last time PISA was conducted, the United States ranked 13th out of 79 countries and regions. The top 10 countries were China (B-S-J-Z), Singapore, Macao (China), Estonia, Canada, Finland, Ireland, Korea, Sweden, and New Zealand).

- In the U.S., the Department of Education (IES) conducts “The Nation’s Report Card” (aka “The NAEP Report Card”) to investigate literacy rates at the 4th, 8th, and 12th grade level. In 2019, grade 12 students’ average reading skills fell two points–with males showing higher declines than females:

According to a subsequent NAEP report card, the decline in U.S. students’ literacy skills in 2019 accelerated in 2022: Remarkably, only thirty-three percent of fourth grade students scored at or above the NAEP proficiency level. Across the board literacy rates fell at the 4th and 8th level (12 grade assessments have yet to be reported): “the average reading score at both fourth and eighth grade decreased by 3 points compared to 2019. At fourth grade, the average reading score was lower than all previous assessment years going back to 2005 and was not significantly different in comparison to 1992.” This is especially problematic because children who cannot read in the 4th grade are 15 times more likely to drop out of school (NAEP Report Card: Reading 2019).

At the adult level, there is further evidence of declining literacy competencies in the U.S.: “According to a 2021 Pew Research survey, roughly a quarter of American adults—including 38 percent of Hispanic adults, 25 percent of Black adults and 20 percent of white adults—say they haven’t read a book in whole or in part in the past year, whether in print or in electronic or audio form. This is even true of 11 percent of adults with a bachelor’s or other advanced degree. These figures are nearly triple those reported in 1978″ (Mintz 2022).

From a social perspective, declines in literacy weaken the social fabric of a culture, creating fragmentation and discord. Without a shared archive, canon, people lack shared religious, political, and historical allusions.

Economic Power

Literacy is strongly correlated with economic power: “In an information economy, reading and writing serve as input, output, and conduit for producing profit and winning economic advantage (Deborah Brandt, D. 2001).

Literacy empower literate cultures to develop new ideas and methods–and more.

In Writing Studies and Media Studies, literacy is perceived to be a technology that transforms consciousness and cultures. For instance, in Orality and literacy : the technologizing of the word, Walter Ong theorizes that literacy empowers cultures to break away from the discourse patterns of orality. Ong argues literacy creates the possibility of sustained inquiry and science; it offers a method for interpreting texts (hermeneutics), creates the need for schooling, and places the spotlight on knowledge as opposed to pathos, which underscores oral discourse. He argues oral cultures tend to repeat the same things over and over again–that the focus is on memory and repetition as opposed to making new knowledge or testing knowledge claims:

Following Ong’s analysis of ways literacy transforms human consciousness and following the emergence of the internet and new media, Gregory Ulmer has theorized that we have entered an Age of Electracy. For Ulmer, electracy functions as a form of entertainment that is experienced subjectively. (See Rhetoric & Apparatus Theory for more on this.)

5. Literacy Refers to a Measure of Educational Attainment and Audience Awareness.

Ultimately, as you have no doubt surmised from the above discussion, literacy functions as a signal of how educated someone is with regards to a discourse community’s conventions and expectations. If you cannot adjust the register of your communications and use the diction, syntax, genres, and media your audiences expects, then you’ll be judged as uneducated or unprofessional.

Types of Literacy

Because the term literacy has been broadened to reference competency in any topic, there are literally hundreds of different types of literacies. Below are a few of the main ones, the ones that matter in academic and workplace contexts.

Functional Literacy

At the international level, as discussed above, world governments focus on functional definitions of literacy–i.e., how well citizens can understand words and sentences and how well they can interpret, make inferences from, and act on what they read across multiple texts. For instance, can citizens understand a newspaper? Can they understand an airplane or bus schedule? Can they read the job announcement and submit a job application?

Critical Literacy

In educational contexts, critical literacy, rather than functional literacy, is the goal. Critical literacy is concerned with rhetorical analysis of power relationships. Critical literacy engages students in metacognition and self reflection about the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of knowledge claims.

Digital Literacy

Digital literacy concerns how individuals navigate and employ digital tools to consume and produce information.

New communication technologies (e.g., the pen, pencil, printing press, internet) alter how people think and conduct themselves–how they collaborate, design, edit, invent, organize, research, and revise documents. As communication technologies evolve, digital literacies create new genres and new media.

Information Literacy

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a capital good such as money or social influence — you need to be strategic about how you consume and use information.

- ACRL Information Literacy Perspectives & Practices

- Archive

- Authority (in Speech and Writing)

- Copyright

- Empathetic Information Literacy

- Evidence

- Information Architecture

- Information Design

- Information, Data

- Interpretation, Interpretative Frameworks

- The CRAAP Test

Quantitative Literacy

Quantitative Literacy refers to the ability to understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute numerical information.

Visual Literacy

“Visual literacy is a set of abilities that enables an individual to effectively find, interpret, evaluate, use, and create images and visual media. Visual literacy skills equip a learner to understand and analyze the contextual, cultural, ethical, aesthetic, intellectual, and technical components involved in the production and use of visual materials. A visually literate individual is both a critical consumer of visual media and a competent contributor to a body of shared knowledge and culture. .In an interdisciplinary, higher education environment, a visually literate individual is able to

ACRL (Association of College & Research Libraries

- Determine the nature and extent of the visual materials needed

- Find and access needed images and visual media effectively and efficiently

- Interpret and analyze the meaning of images and visual media

- Critically evaluate images and their sources

- Use images and visual media effectively

- Design and create meaningful images and visual media

- Understand many of the ethical, legal, social, and economic issues surrounding the creation and use of images and visual media, and access and use visual materials ethically.”

Recommended Resources

Ong. (1988). Orality and literacy : the technologizing of the word. Routledge.

FAQs

What is Literacy?

Literacy — What it means to be literate or to engage in literacy practices — is never a question that can be answered definitively. Why? Because what it means to be literate is constantly changing, evolving. Years ago, if you could correctly interpret a bus map and get to work, you’d be considered literate. In today’s world, you’re not literate — by some community standards — — if you cannot read and write computer code.

Why Does Literacy Matter?

Literacy–broadly conceived of as reading and writing–is empowering, both professionally and personally. Engaging in literacy practices further develops your cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal competencies. Literacy provides a culture, a community, with the capacity to design an archive; to engage in dialog, textual hermeneutics, and research; and to track citations and contributions to human knowledge.

References

“ACRL Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education”, American Library Association, October 27, 2011. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/visualliteracy (Accessed February 11, 2023). Document ID: 4d02961f-23ff-b874-7d6d-9f8d0b87e7c2

Brandt, D. (Ed.). (2001). Literacy, Opportunity, and Economic Change. In Literacy in American Lives (pp. 25–46). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810237.002

National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). (n.d.). Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://nces.ed.gov/naal/fr_definition.asp#:~:text=Literacy%20is%20the%20ability%20to,develop%20one’s%20knowledge%20and%20potential.

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century. J.W. Pellegrino and M.L. Hilton (Eds.), Committee on Defining Deeper Learning and 21st Century Skills, Center for Education, Board on Testing and Assessment, Division of Behavioral Sciences

NAEP Reading: Reading Highlights 2022. (2022, November). NAEP Report Card: 2022 NAEP Reading Assessment. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/reading/2022/

UNESCO. (2006) Education for All: A Global Monitoring Report. Chapter 6: “Understandings of Literacy.” p. 147-159, http://www.unesco.org/education/GMR2006/full/chapt6_eng.pdf

White, S., and McCloskey, M. (2003). Framework for the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2005-531). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/fr_skills.asp