What is Audience?

Audience refers to

- the intended recipient of a message (e.g. readers, listeners, and users)

- an internal dialog that writers, speakers, knowledge workers have with themselves about how their intended audiences are likely to respond to their texts

- a measure of quality in communications

- Texts that are described as audience aware or rhetorically aware may also be described as lucid, clear, or persuasive. Audience Awareness is a defining attribute of persuasive writing and clarity in communications.

What is Audience Awareness?

Audience Awareness refers to

- the degree to which a text is responsive to the needs and interests of its target audience (e.g., readers, listeners, or users).

- A text may be characterized as audience aware, rhetorically sensitive, or rhetorically aware when it

- hooks a reader–when it frames the discourse from the perspective of what the reader, listener, or user most cares about

- adopts an appropriate rhetorical stance, register, diction, tone, voice, and persona given the exigency, the call to write, and the audience, purpose, and topic

- employs the convention and writing style the target audience expects

- provides the story, the organizational schema the audience needs to understand the text.

- A text may be characterized as audience aware, rhetorically sensitive, or rhetorically aware when it

Synonyms

Audience may refer to

- readers

- listeners

- users

and other recipients of a message sent by a Sender (e.g., an author, writer, speaker, knowledge worker)

Audience Awareness may also be referred to as

- audience-sensitivity

- rhetorically sensitivity

- horse sense

Related Concepts: Academic Writing Prose Style; Communication; Composition Studies; Professional Writing Prose Style; Rhetorical Analysis; Semiotics; Tone

When it is effective, writing is rhetorical, i.e., it takes into account the values, ideologies, interests, needs, and commitments of the people, the audiences, for whom it is intended.

NCTE Position Statement: “Understanding and Teaching Writing”

Why Does Audience Awareness Matter?

Audience awareness is one of the most important concerns for any writer, speaker, or knowledge worker.

NCTE’s (National Council of Teachers of English) Position Statement on “Understanding and Teaching Writing: Guiding Principles” (Adler-Kassner et. al. 2018) positions audience awareness at the center of composing (along with purpose and context):

“When writers produce writing, they take into consideration purposes, audiences, and contexts. This leads them to make intentional choices about the elements that go into writing:

- content (the subject or focus of the writing);

- form (the shape of the writing, including its organization, structure, flow, and composition elements like words, symbols, images, etc.);

- style and register (the choice of discourse (aka writing style] and syntax used for the writing, chosen from among the vast array of language systems [often called “dialects”] that are available for the writer); and mechanics (punctuation, citational style, etc.)” (“Understanding” 2022).

Three Perspectives on Audience

In Writing Studies, the term audience or audience awareness may refer to

- the intended reader, listener, and user. Any recipient of a message

- an internal dialog, a thought process, a writer works through when attempting to compose a message for an audience

- a measure of quality writing.

1. Audience as the Recipient of a Message – Audience Addressed

Writers in workplace writing contexts and academic writing contexts are often writing for people who hold specific roles. For instance, audiences may be instructors, users, decision makers. When writing to specific people, writers engage in audience analysis: they question the audience’s unique purposes for reading and listening. They determine how they need to research a topic and respond to the audience by considering the readers’ questions and goals. For example, consider below the succinct example of audience analysis for three audiences: 1. Instructors; 2. Users; 3. Decision Makers.

Instructors

Instructors tend to review and critique student work to

- coach students to provide

- grade student work.

When grading student work, instructors may ask

- Did the student follow instructions?

- Does the student’s work reflect learning and understanding of central course concepts?

- Is the students’ work well written?

Users

Users are focused on understanding instructions or processes. They are not reading for pleasure. In fact, they want to read as little as possible. They prefer visualizations. They tend to be rushed and impatient. When you are writing as the expert, explaining how to do something, your users are likely to ask:

- Can I follow the flow?

- Does the text use a deductive order, deductive reasoning, deductive writing?

- Are warnings and safety precautions clearly presented?

- Can I skim through the visualizations rather than read the text and understand the process or instructions?

- Where can I go for additional help?

Decision Makers

Decisions Makers may be harassed by demands on their time. They may be impatient if you don’t adopt a professional writing prose style. They may only read your abstract, introduction and data visualizations. As readers and users, they may ask:

- Does the writer provide cogent and persuasive evidence for claims?

- Are the research methods credible? Were they improved correctly?

- Can I follow the flow?

- Does the writer use a deductive order, deductive reasoning, deductive writing?

- Is the proposed work feasible? cost effective? impactful?

- What are the economic, social, legal implications?

2. Audience as an Internal Dialog – Audience as a Tool for Invention

Some rhetorical situations are murky. As a writer, you may face situations when you are unsure about what your audience knows and feels about a topic. You may not always be able to make informed guesses about your audience’s level of education, knowledge about the topic, interest in the topic–and so on. As a result, you may need to rely on an internalized, imaginary audience. In other words, you may need to make educated guesses about the needs, education, and likely reactions of the people who are likely to read or listen to your work.

When composing, writers engage in an internal dialog: they imagine, based on their past experiences, their audience’s likely responses to their written and spoken discourse.

For Walter Ong, both reading and writing are acts of fiction: “First, . . . the writer must construct in [their] imagination, clearly or vaguely, an audience cast in some sort of role . . . . Second, we mean that the audience must correspondingly fictionalize itself.” A reader has to play the role in which the author has cast [them], which seldom coincides with [their] role in the rest of actual life (Ong 1975, p 12 – pronouns updated).

“If the writer succeeds in writing, it is generally because [they] can fictionalize in [their] imagination an audience [they have] learned to know not from daily life but from earlier writers who were fictionalizing in their imagination audiences [they have] learned to know in still earlier writers, and so on back to the dawn of written narrative” (Ong, p. 11)

In other words,

- writers create an ongoing internal dialog with themselves and an imagined audience. They ask themselves how they believe the intended audience would most likely respond to a particular exigency or compositions.

- “The historian, the scholar or scientist, and the simple letter writer all fictionalize their audiences, casting them in a made-up role and calling on them to play the role assigned (Ong 1975, p. 17).

- audiences play a role when they interpret the writer’s text. As readers they attempt to adopt the

mindset they believe the writer wants them to play. From this perspective, audience awareness is much more than deciphering the needs and interests of real readers: it’s an invention tool, a heuristic that guides the creative process: “The central task of the writer, then, is not to analyze an audience and adapt discourse to meet its needs. Rather, the writer uses the semantic and syntactic resources of language to provide cues for the reader—cues which help to define the role or roles the writer wishes the reader to adopt in responding to the text” (Ede and Lunsford, p. 160).

3. Audience as a Measure of Quality

Audience may also be used as a measure of clarity in writing and overall writing quality. Works that are judged to be audience-sensitive tend to be highly valued: “When writing reflects the expectations that audiences have for each of these elements [content, form, style, register] it is considered good; when it does not, it is considered less than good—and often the writers who produce it are judged accordingly” (NCTE 2018).

Audience awareness is so important to denoting quality writing that the term “reader-based prose” is synonymous with quality writing. In contrast, “writer-based prose” denotes works underdeveloped or poor writing.

Audience Analysis – How to Analyze Your Audience

To be effective at audience awareness, you need to embrace information literacy perspectives and practices, especially strategic searching and empathetic information literacy.

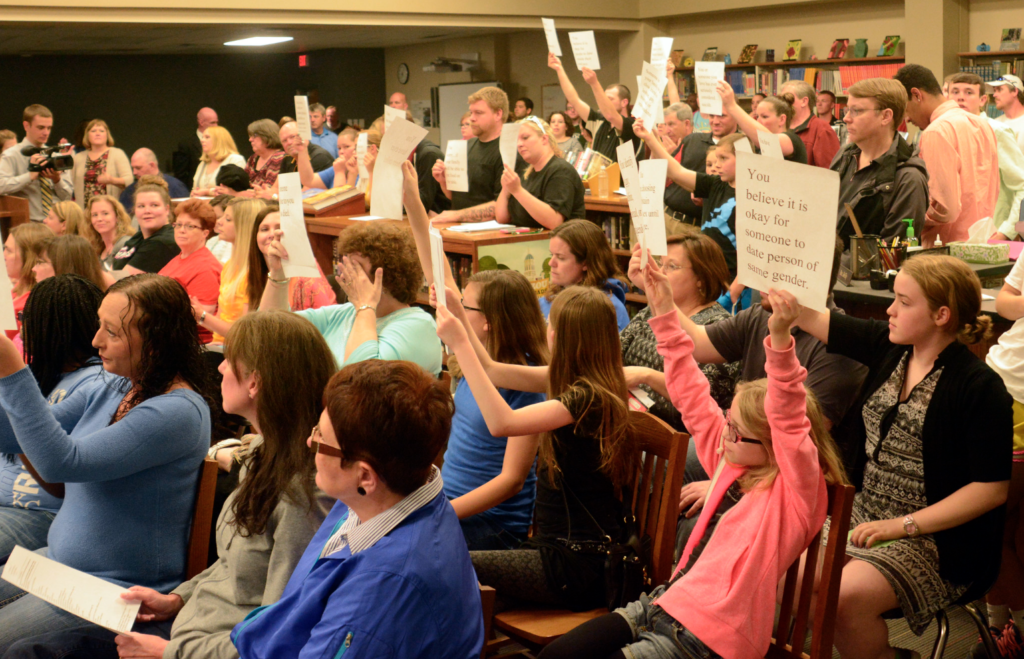

Sometimes you may violently disagree with your audience. On such occasions, you may find it difficult to set your own strongly opinions and ideas aside. However, even if you’re unlikely to change your thoughts and feelings about something, you can still benefit by understanding your audience’s perspective.

Audience Analysis Questions

- Who is your target audience?

- a teacher? a parent or loved one? fellow students? a politician? a university committee? a broad, general audience such as subscribers to Substack or Medium?

- What are the audience demographics?

- Language? Dialect? Register? Age? Gender? Income level? Educational level? Political associations? Cultural associations?

- Does your document have multiple audiences? Can you discern an important secondary audience?

- Would it be helpful to provide have separate sections in your document to address the unique needs of your different audiences?

- Do you need to distribute your message through multiple channels to reach your disparate audiences?

- How knowledgeable is your audience about the subject?

- What concepts or terms do you need to define for your audiences?

- How open is the audience to the information you are sharing?

- How aware is your audience of the current scholarly conversations about the topic?

- What types of evidence is your audience likely to view as authoritative?

- What counter arguments will your audience hold that qualify or refute your position.

- What are the prevailing scholarly conversations on the topic?

- What interpretive lens is your audience using when they read your texts?

- How interested, how motivated, is your audience?

- What genre, media, apps do you need to use, if any, in order to reach your target audience?

- What particular style of writing, genre, tone, diction does your audience expect you to use?

When Should I Engage in Audience Analysis?

In general, you should engage in audience analysis (and analysis of your rhetorical situation) early during composing–as a form of invention or prewriting.

However, there can be exceptions. For instance, in interviews (see e.g., The Paris Review Interviews), some fiction writers and poets say they don’t think much about their readers when they write. Instead, they say they are writing for themselves. And some writers prefer a stream-of-consciousness approach to composing. They don’t want to run the risk of stopping the creative flow to ask critical questions about how, e.g., a reader would be likely to respond to a bit of information.