As a college librarian, Patricia Knapp worked with many students who were new to academic research and writing. She observed that beginning students often “have a basic misconception of the function” of research: “they look for and expect to find ‘the answer to the question’ instead of evidence to be examined” (as quoted in Kuhlthau, 10).

Don’t worry if you’ve ever harbored the mistaken belief that research is all about finding the perfect source, a book or article that completely answers your research question. Experienced researchers fall into that way of thinking, too! But they’re also able to step back and rethink their approach to a research question–they’re able to “divide and conquer.” Here’s an example:

Our research question is: How can virtual teams be implemented at Pixar Animation Studios?

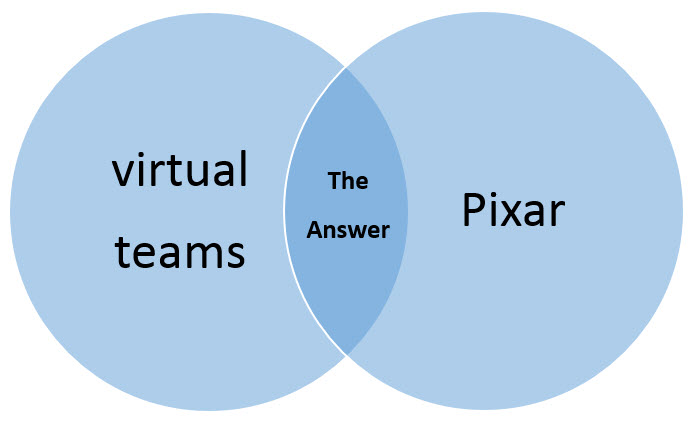

You might want to dive right into a library database to find “the answer” to the question, with a search like this:

“virtual teams” AND Pixar

And you might think that such a search will find a ready-made answer to the research question, as represented in this Venn diagram:

But the facts are: a) probably no one has ever published an article about virtual teams at Pixar, so the search would yield zero results, and b) research isn’t about finding “the answer”–it’s about finding ideas and facts you can use to create your own answer.

You should divide the question into two parts, in order to conquer it:

- First research virtual teams (their challenges, best practices, etc.).

- Next research Pixar (its mission, corporate culture, etc.).

Accordingly, your two separate database searches might look like this:

- “virtual teams” AND (challenges OR “best practices”)

- Pixar AND “corporate culture”

A journal article that you might choose from the first search is by Soo Jeoung Han et al., “How Virtual Team Leaders Cope with Creativity Challenges,” in which the authors study ways that creativity can be fostered in virtual teams. From your second search, you might use an article from Harvard Business Review by Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull, “How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity.”

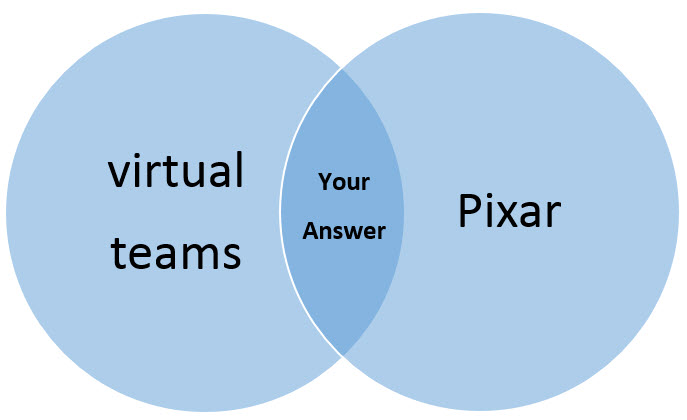

By putting these two texts—Han et al. and Catmull—into conversation, you can begin to develop your own argument about how virtual teams could be implemented at Pixar. You might begin with the observation that, according to Han et al., the qualities of an effective creative team are the same, whether it is a virtual or an in-person team. Because, as Catmull notes, Pixar already has such a strong team culture, the company would be well positioned to implement virtual teams: they have formed close relationships, strive to create a space where it’s safe to bring up new ideas or critique others’ ideas, and group members at all levels of the company support one another and take on leadership roles. You could lay out some of the promising parallels between Han et al.’s key findings and the vibrant group culture at Pixar.

Once you’ve started putting the two texts into dialogue, you would probably see more connections. For instance, one of Han et al.’s most interesting claims is that using state-of-the-art technology to communicate can be a motivating factor in itself. Catmull tells us that, at Pixar, “Technology inspires art, and art challenges the technology” (71). Given the fascination with technology at Pixar, members of virtual teams would be motivated to participate because of the opportunity to experiment with the newest forms of digital communication.

By orchestrating an interplay between your two sources, putting them in dialogue with each other and with your own ideas, you can offer an original analysis. “Conquering” your paper means offering this analysis—your thinking, visible on the page. This is what professors—and all genuinely interested readers—want to see.

Speaking again in Venn, the process of creating your own answer to the research question looks like this:

Divide:

Conquer:

The rhetorician Kenneth Burke famously described academic writing as a conversation that has been taking place among various authors, across time, on a given topic; it’s your job as an academic writer to add something new to this conversation. You may think of academic writing and creative writing as completely separate, especially if you’ve been taught to exclude your own voice and opinions from school papers. But when you “divide and conquer,” looking for evidence that can help you to contribute an original idea, academic writing is creative.

Works Cited:

Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action. New York: Vintage, 1957.

Catmull, Ed. “How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity.” Harvard Business Review, vol. 86, no. 9, Sept. 2008, pp. 64-72. EBSCOhost.

Han, Soo Jeoung, et al. “How Virtual Team Leaders Cope with Creativity Challenges.” European Journal of Training & Development, vol. 41, no. 3, Apr. 2017, pp. 261-276. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1108/EJTD-10-2016-0073.

Kuhlthau, C. C. Seeking meaning: A process approach to library and information services. 2nd ed., Libraries Unlimited, 2004.